Weesp and Rembrandt 2019

In March 2019 I visited the Netherlands. I had come to the Netherlands in search of beautiful things. First, I planned to attend a stamp auction in the town of Weesp a little outside Amsterdam, and here I hoped to acquire some desirable and beautiful stamps and letters for my collection. Second, I wanted to see the exhibition Alle Rembrandts in the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum which gathered all the museum's Rembrandt paintings, twenty-two of them, together with hundreds of sketches and etchings, in commemoration of the 350 years anniversary of the painter's death.

I have always had a strong affection for Dutch people, in the sense of love, not so much because they are the tallest people in Europe and they invented the orange carrot, but more because people there are supremely hospitable, easy-going, and fun-loving - Oh! and they're serious about stamp collecting too, like me, which is why I went to attend the stamp auction of the Nederlandsche Postzegel Veiling in Weesp in March 2019. I had never been to Weesp before, but was immediately struck by the beauty of the town with its protected historical center and fine examples of 17th and 18th century architecture. Archetypically Dutch, the town is lined with canals with many traditional half-timbered lift bridges, and there are three old windmills. Having flown in from Hong Kong, I awoke far, far too early at 4 am, and decided to walk through the center of town, like many Dutch towns so perfect for walking and cycling. Aside from one or two people walking their dogs, I learned that Dutch people are mostly inside their homes at this early hour. But birds are active and make sweet melody and ducks paddle up and down the canals without a care in the world. I took a few pictures from my morning tour of Weesp, as the sun was rising and the fog lifting from the canals. I show my pictures here without much commentary.

In the periphery around Amsterdam is a ring of military fortifications known as the 'stelling van Amsterdam', a defensive and fortified water line from which the lowlands could be inundated in the event of an enemy attack. One of the forts is found in Weesp. The ring of fortifications was constructed between 1880 and 1920. The line has never seen combat and the use of aircraft and heavy tanks had rendered it almost obsolete by the time it was completed.

'Jugendstil' in Weesp. I'm unsure what this building is.

The old and broad-shouldered Maarten Lutherkerk on Nieuwstad 36 functions today as the towns dental clinic. Truly.

Alle Rembrandt

Amsterdam Rijksmuseum

Self-portrait by Rembrandt the expressionist!

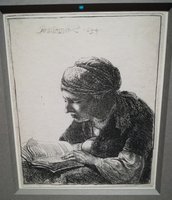

Woman reading. An etching from 1634. Rembrandt could create dramatic shadows with ink on paper as much as he could with paint on canvas.

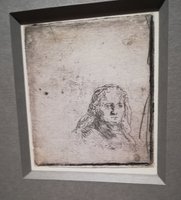

Rembrandt and Saskia 1636. Rembrandt married Saskia in 1634 and she appears in many of his paintings and drawings. Saskia died in 1642 a short while after giving birth to their son Titus.

In the Rijksmuseum, my attention was caught by this pair of private etchings of Saskia, one produced when she was alive, the other after she had died in 1642. They constitute two different forms of representation, it seemed to me, showing Saskia as she would have walked around Rembrandt when he was working, and as he remembers her, after her life had been extinguished, looking to the side with a vacant gaze.

We live in an intensely visual age, everyone is a photographer, and every day we are bombarded with pictures from all angles. Most pictures we are exposed to are of questionable quality and a great deal are commercial, served to us by people not because they love us but because they want our money. So, sometimes it is useful to remind ourselves what good pictures really are and what our humanity was once able to produce, even if from a very distant past. For that reason I journeyed to Amsterdam to see the Alle Rembrandts exhibition, a chance of a lifetime to see a comprehensive show of the master's paintings and drawings. It was a great experience, not so much because it showed us what a masterful painter Rembrandt was (we knew that already!) but because it shows important paintings in the context of the hundreds of drawings and etchings that served as preparatory exercises for these paintings, and in which Rembrandt experimented and improvised with the representation of emotions and expressions.

The Jewish Bride

The identity of the couple is uncertain but it could be an Old Testament couple (perhaps Isaac and Rebecca of Genesis 26: 8). Rembrandt painted the picture circa 1667, a year or so before his death. At this time he didn’t have to prove anything, but gave himself away to considerable idiosyncracy of theme and technique. He applied a thick paste of paint in heavy, coarse brushstrokes to create the texture of dress and the roundness of the jewellery. Laying on such massively thick coats of paint gives the painting an almost sculptural quality. Maybe Rembrandt felt he should use up his last remaining paint towards the end of his life...

Seeing this painting up close in the Rijksmuseum is a dizzying experience! The brown and crimson earthy tones flicker in intensity, and one can notice how Rembrandt applied paint with a palette knife and scratched into it with the butt end of his paintbrush to give realistic folds in the clothing. We may think of painting as a delicate, refined and detailed process, but it could also be intensely physical work. When Rembrandt scratched and rubbed on this canvas it must have resounded through his workshop in his Amsterdam canal house; perhaps passers-by in the street below could hear the master hard at work in the studio.

Vincent van Gogh saw Rembrandt's painting in the Rijksmuseum and was moved by the intimacy and tenderness of the painting; “I should be happy to give ten years of my life if I could sit in front of this picture for a fortnight, with only a crust of dry bread for food.” In the painting a hand is placed on a bosom not out of lust but out of affection. The painting does not have the lightness of a seduction scene, but the gesture shows tenderness, affection and protection (it has been thought this is a painting of a father blessing his daughter on her wedding day, which is, I suppose, a possibility) – it is a painting of subdued emotion; the figures appear melancholy and to me sadness seems the prevailing sense. The figures make no eye contact but seem preoccupied with their own meditations. When I saw the painting in the Rijksmuseum, I felt sure that the figures were contemplating their own mortality and coming to understand that each person alone must attempt to make sense of it.

Rembrandt's self-portraits

The quantity is remarkable: we have close to 100 self-portraits (drawings, etchings, and paintings) that form a visual auto-biography which explores and shows the realities of growing older and aging. In the paintings, Rembrandt confronts us directly and is often dressed in fancy costumes, for example aristocratic costumes, costumes a hundred years old by the time he paints, and exotic oriental attire. In these paintings he appears to ask questions about the very nature of identity. If I was born a hundred years earlier, or if I were an oriental potentate, would I still be an artist? And what kind of artist could I be? A man can be many things indeed and a stable idea of selfhood is perhaps a fiction. As Rembrandt confronts us directly in his paintings he urges us to know ourselves better and to ask ourselves similar questions about identity.

To regard Rembrandts series of self-portraits, produced rather evenly through his career, as painting’s equivalent of an interior monologue – as a rigorous self-reflection and contemplation – is probably a Romantic stereotype that would have made little sense to Rembrandt. Instead the paintings were produced for a ready market, and appealed to well-heeled buyers who desired expressive paintings with display of remarkable technique and virtuoso representation of emotion. Buyers also liked to have paintings of famous people, and Rembrandt was a famous person. These buyers could possess a painting by a recognized master and they could marvel at, and show off to their friends, artworks that show the texture of flesh and clothing convincingly and make it glow with light and vibrant colour.

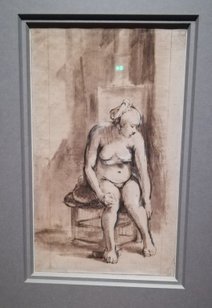

Rembrandt and his students painted nude models in Rembrandt's studio. As the temperatures were often low, the models posed in front of an oven to keep warm. Painters did not usually include the oven in their drawings as Rembrandt did here. He departed from decorum in several ways.

Rembrandt, 1630 (aged 24)

Rembrandt the poser! Rembrandt dressed up as an oriental prince wielding a dramatic-looking Kris knife.

Rembrandt delighted in dressing up and in rendering clothes; in fact he made clothing an integral part of his representation. We know that he had his own costume collection in his house and acquired many exotic artifacts. Sometimes he would dress up his son Titus and wife Saskia in exotic dress to paint them. They must have had a right laugh! (I like to think, a bit like teenagers dressing each other up before going to a fancy dress party.)

Dutch citizen and every tourist to this fine land go to see Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, like pilgrims flocking to Mecca. The Rijksmuseum appears built around the painting, to be found in the so-called Gallery of Honour which, as is clear to all who enter it, is designed to look like the nave of a cathedral, in which the colossal painting occupies the place of the altar. For me, the painting is a difficult one to love, truly, but I think I have decided to appreciate it as a genre painting that succeeds in subverting its genre.

The Night Watch, 1642

I first saw Rembrandt's Night Watch as a teenager when I travelled to Amsterdam with my father and sister. I don’t remember liking it very much back then – or, more accurately, I remember not liking it very much. I found the painting bewildering; I couldn't make heads or tails of it, and my eyes moved around to find rest, to find something to fix the gaze on. I think this was quite an astute first response.

On my second visit to see The Night Watch in 2019, my impression remained pretty much the same, I admit. The painting, which shows a citizen militia company of an Amsterdam district, is of colossal size with the figures nearly life-size, and I felt that it teeters on the brink of chaos and anarchy. A boy is running, a drummer drumming, a dog is barking, a soldier fires his gun in the middle of the crowd by mistake, banners are waved awkwardly, people get in each others’ way, and guns, banners, poles, and spears point in every direction. If we think of this animated and “noisy” picture as a photograph, the sense is that the second after the snapshot is taken the unruly group will have moved around or marched off entirely. Outrageously, the young woman in the center of the painting, which information in the museum explained was a mascot for the militia who carries their symbols and emblems, appears to be completely ignored, even pushed to the side and nearly trampled on by the militiamen. She is a striking apparition, more like a radiant saint, ethereal, lit from within (I thought she might perhaps represent Saskia, Rembrandt’s wife who died in the year of the painting’s completion – the figure has the same slight double chin that we see in Rembrandt’s other paintings of Saskia).

Coming to see this a second time, I felt that I was looking at a deeply ambiguous painting, with probably a comic intent behind it. Group portraits of militiamen were an established genre of painting at Rembrandt’s time: most often they show a stiff, formal line-up of formidably self-satisfied figures in their finest attire. But it was in Rembrandt’s nature to subvert or at least challenge the norms of the art that had formed him. He must have felt it futile to follow tradition by presenting a static tableau. Knowing that a part-time militia guard served mainly a ceremonial function, and was made up of well-heeled men who socialized, dined and drank, and occasionally practiced their shooting skills, he decided to poke some fun at these ambitious Amsterdam burghers, who commissioned the painting collectively but would have paid individually to be included in it. I’m not sure how the painting was received when it was unveiled in 1642 but I imagine it must have caused considerable controversy. In a sense, they all got what they must have expected from the famous Rembrandt: a painting that shimmers with movement and dramatic light; a depiction that is theatrical and flamboyant, imbued with drama, in which the light is powerful and reflected unto faces.