Thomas Connary (1814-1899), Stratford, New Hampshire

Irish immigrant to the United States, farmer, bibliophile, and prolific annotator of books

In 2008 I acquired a collection of 30 annotated books that once belonged to an Irish immigrant to the United States by the name of Thomas Connary. Examining this material offered fascinating insight into the personal history of one Irish American, into the nature of his Irish Catholicism, and into how books could structure religious beliefs and social life. In 2014 I published Books and Religious Devotion: The Redemptive Reading of an Irishman in Nineteenth-Century New England with Pennsylvania State University Press, a detailed chronicle of this person's universe of books.

This display shows examples from Connary's many richly annotated and decorated book, and tells more about the personal history of this New England farmer. I also show my collection of old postcards from Stratford in New Hampshire where Connary lived for more than 50 years.

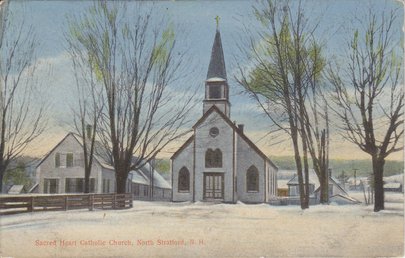

Thomas Connary immigrated to the United States in 1833 at the age of 19, and settled in the town of Stratford. He lived in the family farmstead with his wife Lucinda and their five children Joseph, John, Simon, Mary and Anne. The Connary family were the first resident Catholics in the Stratford community, and Thomas Connary purchased the land on which the Sacred Heart church was erected in 1887.

Were if not for the accidental survival of his books and writings, Thomas Connary would be well-nigh forgotten: a distant and forgotten ancestor; a name on a tombstone; one individual among the millions who emigrated from Ireland in the nineteenth century in search of new experience and a better life.

Thomas Connary collected books and inserted much of his own writing into his books, which he understood as durable objects that would be treasured by his family for many generations to come. By enhancing books with much of his own writing addressed to his family he managed to turn them into vessels of moral edification and spiritual guidance. Books become repositories of family history and recollection of the past. Knowing that a consciousness of Irish history and identity is a tenuous one and not easily sustained in a family without first-hand experience of the country of origin, Connary used his books to convey a wealth of information about genealogy, people, and places in Ireland.

The process of decorating and annotating books provided Connary with an opportunity for creativity and even for asserting himself as an author. Writing inside books meant to share precious memories of early schooling and religious education in Ireland. It meant also to share reflections on the religious and moral life, and even to record dreams and spiritual experiences. The books preserve abundant traces of past acts of reading and they dramatize the routines and desires of lived spirituality. When we study this kind of material in detail, the voice of a dead person comes alive and bequeaths us rich insight into a group of individuals that we too rarely regard as active creators and agents (often because so little material has survived).

Thomas Connary worked as a farmer in Stratford, and it is in old age (from about the age of 60) that he turns increasingly to the activity of decorating and annotating books, a discipline that he refers to as his "Book keeping". In old age Connary found it increasingly difficult to travel the ten kilometres to the nearby Catholic church, so we may see his labour in books as a deeply enriching devotional activity that served as a form of alternative to a direct involvement in the local parochial scene.

Connary also saw some meaningful parallels between his previous work experience and his prayerful enhancement of books. Being habituated with the manual labor of cultivating the fields, Connary rejoiced in old age that his books provide him with ample space to cultivate for the spiritual health of himself and others. Looking at his sizeable collection of religious literature he notes, "here we have millions of acres of Book room". As he labours across the topography of the page, his reading and writing become a form of ploughing, moving from left to right, and often working its way round the page. His writing spirals around the printed text, so that one needs to rotate the book to read it. This is a manual cultivation carried out inside books, full of implication for salvation and the moral life.

Books and Religious Devotion

Books and Religious Devotion is a study of a remarkable book collection of a nineteenth-century New England farmer, Thomas Connary. Through a detailed reconstruction of how this lay Irish Catholic read and annotated his books, the study gives new insight into the capacity of books for structuring a life of devotion and social participation, and it presents an authentic and holistic view of one reader’s interior life.

The Revelations of Divine Love, written by Julian of Norwich in 14th century England, was one of Connary's most treasured books. He purchased this American edition shortly after its publication in 1864, and he annotated the volume during more than three decades. Most of his annotations occur on the book's blank pages or on interleaved notebook pages.

Connary did not just insert his own writing into books, but also decorated his books with images and poetry sourced from different newspapers and magazines that he subscribed to. In this example from James O'Leary's History of the Bible (New York, 1873), he inserted images and poetry on the Resurrection of Christ -- a form of aesthetic enhancement of the book.

Like so many Irish immigrants in the US, Connary never returned to his native country. But as this inserted advertisement for tickets by White Star Line steamer (later of Titanic fame) to the 'Old Country' shows he may well have considered it. Pasting this fragment into Pope's The Council of the Vatican (Boston, 1872) indicates a nostalgic longing and may provide Connary with some imaginative link to Ireland.

Partaking in a well-established tradition of producing scrapbooks, Connary inserted miscellaneous material into his many book. In The Council of the Vatican are found his characteristic spiraling handwriting on religious themes and a short printed article on the achievement of Christopher Columbus. Much of his reading of magazines and newspapers was done with scissors in hand.

On the front flyleaves of The Sinner's Guide, printed in Philadelphia 1845, are found biblical illustration, printed poetry, and handwritten prayers and religious exhortations addressed to Connary's children. The blank pages of a book can provide opportunity for creativity and moral edification.

A blank page in the Fundamental Philosophy of the Spanish theologian Balmes, printed in New York 1858, accommodates an eccentric mixture of religious prayer, philosophical reflection, and moral guidance to Connary's children.

In the rear of O'Leary's History of the Bible is found an anthology of inserted religious pieces. Connary adds the page number 250 in hand and thus extends the book's pagination: to him, the book does not end with the conclusion of the printed text!

Connary took an active interest in contemporary social and political topics. Pasted across the printer's advertisements at the back of Haskins's Travels in England, France, Italy and Ireland (Boston, 1856) is an article on a long-lived theme, “Hanging as a Means of Punishment – Does it Prevent Crime and Increase Morality?” The article does not denounce the death penalty per se but argues for the application of science to “humanize and revolutionize the barbarity of the scaffold”. Two years after the article was published the electric chair was used for the first time in the American penal system. Connary remains silent on the matter of the death penalty, but obviously took an interest in the subject.

Thomas Connary on his family history and his decision to emigrate. From a note written in 1886 and inserted in St. Francis of Sales, The True Spiritual Conferences (London, 1862)

My Father Simon Connary born in Ballycallen, 4½ miles westerly from Kilkenny City, Kilkenny County, Leinster Province Old Ireland, February 20 1785, died Lisdowny, in said County and province, December 12, 1825, aged 40 years, 2 months, 8 days if I count my figures right. I, Thomas Connary, was born in Aquaregar, near Lisdowny, May First day, 1814, my Family homestead was in Castlemarket in said Kilkenny County, near Ballinakill, in the Queen’s County, during the full time we lived in Ireland after my Father’s death. Castlemarket is near Ballinakill Roman Catholic Church, in Ballyragget parish. I left my Castlemarket home and family early in the morning March 25, 1833, expecting to go to the County Kerry to remain there at school a few months, then to return to my Castlemarket home and Family. On the way I met a few people who were on the way to America, I accompanied them, and worked for Mr Josiah Bellows 2nd, and his family, in Lancaster, Coos County, New Hampshire in June that year, my home from that time to this day has been in the United States of America.

Connary on his love of books and the power of books to function as religious icons. Note from 1890 inserted in Julian of Norwich, Divine Revelations (Boston, 1864)

I have many Books and cannot think that I can ever be really happy anywhere without them: you will see that I speak of happiness now in this small paper, and when I speak of happiness in it, I speak of eternal everlasting heavenly happiness alone in it. For this one business purpose alone I love my Books, and for no other business purpose, from time I was born to this Wednesday February 12, 1890, I have loved my Books well only for the power which they give to me to have a heavenly home with our divine Creator continually for unending eternity. This way alone of Book keeping is God’s way to prosperity and heavenly happiness unending.

Extract from

Books and Religious Devotion: The Redemptive Reading of an Irishman in Nineteenth Century New England

(thanks to Pennsylvania State University Press for their permission to publish from my recently published monograph on this website)

Preface: A Discovery and Serendipitous Journeys

The seeds of this research project lie in the collector’s instinct. Having spent years researching the religious writing and devotional culture of the Middle Ages, I developed an additional interest in collecting early printed editions of medieval religious and mystical writers, primarily from England. These small-scale collecting endeavours concentrated on the writings of the so-called Middle English mystics, including Walter Hilton, Richard Rolle, Julian of Norwich, and Margery Kempe, writers active in the fourteenth century and the first half of the fifteenth. Many of these early texts were made available in print in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, at a time when English Catholic scholars promoted a new energy of spirituality and did much to revive interest in England’s religious past. I had long desired a scarce nineteenth-century American edition of Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love printed by the Boston printers Ticknor and Fields in 1864. I had placed the book on a wants list with one of the biggest online marketplaces for rare and used books, and in the spring of 2008 an email alert was received that the book was available from an American bookseller in the small town of Bridgewater, Vermont. Part of the online book description ran as follows:

The contemporary binding is firm. However, the previous owner of the book dating to the 1870s and 80s has inserted handwritten notes of a religious theme into the book and pasted numerous newspaper clippings onto blank areas. These clippings, however, do not affect any of the original text and make for some interesting reading of that time.

This was read with a mixture of curiosity and mild annoyance: curiosity of course about what a nineteenth-century reader (presumably American) would import into a copy of Julian’s Revelations and what the “interesting reading” might be, but also some disappointment that the book came with such invasive readerly addition when all I wanted was a tidy copy of a medieval text familiarly known to myself printed in the United States at the time of the Civil War. Conceivably, the bookseller thought along similar lines: the repeated “however” in the description above, the firm reassurance that the insertions do not obstruct the printed text, and the very moderate price of the book all betrayed some assumption (shared by me) that collectors of antiquarian books prefer the pristine, unblemished copy.

What arrived in the mail from Vermont intrigued me. The copy of Julian’s Revelations once belonged to an Irish immigrant to the United States, and this individual, clearly a Catholic of strong religious devotion, had converted the book into a repository of miscellaneous objects, including several newspaper articles, some private letters, and extensive handwritten religious reflections of a didactic and rather idiosyncratic nature. An email exchange with the seller ensued, and within a year I had purchased more than thirty volumes from the same collection, all containing the same Irish-American owner’s imports and annotations. The seller could reveal little about the provenance of the collection: it was bought from an estate sale in Vermont, and the books “were all packed into a trunk and had obviously been there for some years.” The truth of this latter observation was confirmed by the layer of fungal growth found on several of the book covers and by the fact that the books were inhabited by a thriving colony of minuscule book-feeding insects (probably the so-called booklouse of the psocoptera order) that greeted me whenever a book was opened, but which then sought refuge behind the spine to feed on the paste used inside the binding). Moreover, according to the bookseller, several volumes from the same estate had already been acquired by other buyers and collectors. I was provided with the relevant titles, but I never had the opportunity to examine these “lost” books myself (the appendix lists the full range of titles). It became clear early on that something had to be done with this material, which arrived in several installments over an extended period from my contact in Vermont. This study is an attempt to make sense of the phenomenon that was presented to me in this way.

If any term characterizes the inception of this project, and the trajectory of curiosity-driven research that was to follow, it must be that of serendipity. This idea captures the progressive questioning that advanced this project, leading into what was for me unfamiliar and unexpected research territories, such as the Irish diaspora, nineteenth-century Irish-American print culture, the religious culture of New England, the local history of Coös County in New Hampshire, and the history of psychiatry in North America. There may be a tendency today to de-emphasize the significance of serendipity in academia (although we continue to cultivate myths of chance discoveries in science and other areas), but in this study the idea has to be foregrounded. What follows, charts a serendipitous journey and the evolving understanding and appreciation of an acquired collection of annotated books.

Derived from an ancient Persian tale, Horace Walpole’s peculiar eighteenth-century coinage, “serendipity,” refers to a story about a journey. In the words of Walpole:

I once read a silly fairy tale, called the three Princes of Serendip [a medieval Persian name for Sri Lanka]: as their Highnesses travelled, they were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of: for instance, one of them discovered that a mule blind of the right eye had travelled the same road lately, because the grass was eaten only on the left side, where it was worse than on the right … (you must observe that no discovery of a thing you are looking for comes under this description).

There can be no doubt that when Walpole coined his curious neologism he had in mind the serendipitous discovery of the Sherlock Holmesian type: the three princes, sent out by their father King Jafer of Serendip to gain the practical experience that would complement their deep book learning, use their keen powers of observation to make subtle inferences from clues and traces which to others may go unnoticed or appear trivial. Thus employing skills in detection, the three princes provide inferential reconstruction about that which remains unseen.

With time, the meaning of the term “serendipity” has broadened to describe processes of discovery beyond the methodology of the subtle, detective-like inference from signs. We might find patterns of serendipity in planned discoveries and in the systematic investigation of the research project, in which one may set out in search of something without knowing exactly what will be found. We may dip into the archives to examine a particular corpus of material, conducting directed research while more or less expecting to find the unexpected: “systematic, directed (re)search and serendipity do not exclude each other, but conversely, they complement and reinforce each other.” Another form altogether of discovery by serendipity is the happy accident in which something is found but unsought. This is the chance discovery – inadvertent, unanticipated, fortuitous – happening when we do not look for it, or are in search of insight of another kind.

The discovery of annotated books that is the subject of this study is manifestly of this last category of serendipitous finding. It also reflects Walpole’s understanding that “no discovery of a thing you are looking for comes under this description.” The decision to allow myself to become serendipity-prone – to follow, as it were, the path of the princes of Serendip – meant to trust an early intuition that the material that more or less dropped into my lap presented some measure of cultural and intellectual significance. It meant also letting the chance discovery develop into a structured research project: to employ the finding academically and sagaciously (to use Walpole’s term), meant to explain, argue, theorize, categorize, and contextualize on the background of a serendipitous discovery. First and foremost, however, the process was one of sharing an experience with the original owner of becoming intimate with books and, through them, with the owner’s pious and earnest voice. These books, which had lain dormant for decades, preserve traces of past passion and sincerity, and what follows is in part an attempt to reawaken the voice of a past reader and to mobilize a measure of sympathy with him (by which I understand a sympathy of comprehension that seeks to understand the motivation for his bookish labours, not so much a sympathy of either pity or approbation). The name of this individual is Thomas Connary and he emigrated from Ireland to the United States in 1833 at the age of nineteen. In fact, like any good serendipitist, Connary himself ventured forth alone in a manner inadvertent and fortuitous. As will be clear in what follows, he embarked on an unplanned journey across the Atlantic by an unanticipated route; he went where chance brought him, assisted by people he did not know well.

Stratford, New Hampshire

Stratford is located on the Connecticut River on New Hampshire’s north-western border to Vermont. Comprising the two settlements of North Stratford and Stratford Hollow, the town was granted its charter in 1762 under the name of Woodbury: this charter was re-granted in 1773 with the name of Stratford in memory of Stratford-on-Avon, probably via Stratford, Connecticut, from where some of its earliest settlers had come.

When Thomas Connary settled in Stratford in 1846 this was a town of around 500 people. In this rural New Hampshire setting, which prospered as a farming and logging centre, especially with the coming of the Grand Trunk Railway in 1853, Connary lived in his family farmstead with his wife Lucinda and their five children Simon, Mary, John, Joseph, and Anne until his death in 1899.

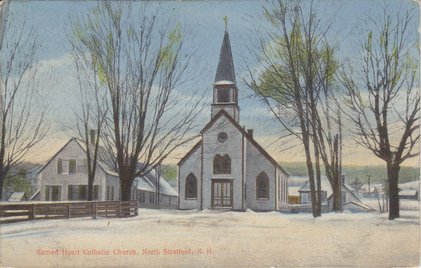

Stratford Sacred Heart Church on Main Street in North Stratford. Unused postcard c. 1920. Thomas Connary bought the land on which the church stands in 1866: the church itself was completed in 1887.

The Baptist Church on Main Street in North Stratford, used postcard dated Sep. 1906. This church was destroyed by fire on Easter Sunday in 1915. A new church was completed in Jan. 1916 and stands till this day.

The view of North Stratford, 'looking West from Stevens Hill'. Used postcard dated Aug. 1908. The Baptist and Catholic churches on Main Street can be clearly seen.

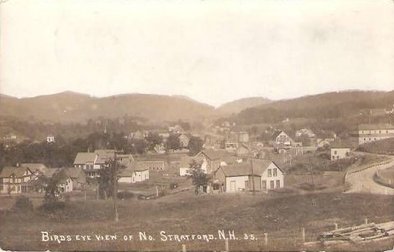

A 'bird's eye view of North Stratford, NH' (admittedly of a low-flying bird). Unused postcard, c. 1910.

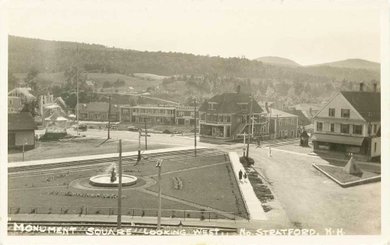

North Stratford, 'Monument Square looking west', unused postcard, uncertain date c. 1930 (not in my collection).

Sacred Heart Church, unused postcard c. 1910. On one of the stained glass windows in the church is remembered Thomas Connary, Stratford's first resident Catholic who bought the land on which the church is erected.

The view of North Stratford from Hutchins' Reservoir, used postcard from Feb. 1906. The picture is taken from the Vermont side of the Connecticut River, and the spire of the Sacred Heart Church on Main Street in North Stratford is visible.

The Connecticut River, separating Bloomfield, VT and North Stratford, NH. Just visible is the Catholic church in Bloomfield, like the Sacred Heart Church in North Stratford erected on land purchased by Thomas Connary.

The public school in North Stratford, erected in 1884. Unused postcard c. 1910.

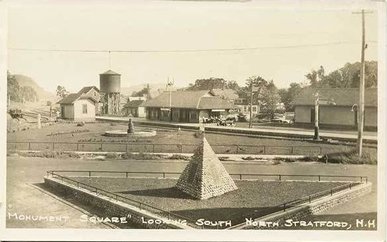

North Stratford, 'Monument Square looking south', unused postcard, uncertain date c. 1930 (not in my collection).

The location of the Connary homestead in Stratford Hollow. The map is found in Jeannette Thompson's History of the Town of Stratford, and it shows Stratford in 1861.

An invitation to participate in the conviviality and merriment of Stratford's 200th birthday celebration in 1974. The festivities extended from August 2nd - 5th and included an historical pageant with the title of 'Stratford's Yesterdays' and a beard judging contest. Published to mark the occasion was A Pictorial History of the Town of Stratford, New Hampshire on the Occasion of her 200th Birthday.

Comprising the two settlements of North Stratford and Stratford Hollow, the town was granted its charter in 1762 under the name of Woodbury: this charter was re-granted in 1773 with the name of Stratford in memory of Stratford-on-Avon, probably via Stratford, Connecticut, from where some of its earliest settlers had come.