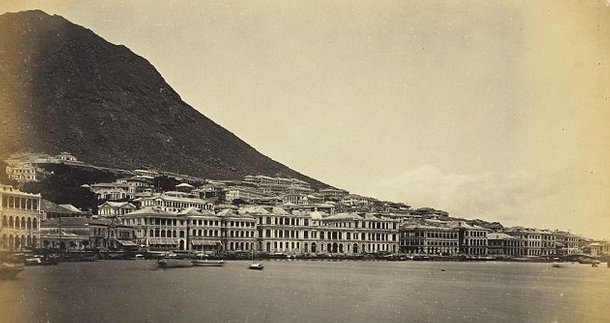

The Peak, Hong Kong, c. 1870

(prior to planting of the Peak)

A Brief Interview with Mr Charles Ford

(This story is an imagined interview with the Hong Kong Superintendent of Government Gardens, Charles Ford, who lived and worked in Hong Kong from 1871. During his dedicated service in Hong Kong, Mr Ford published very comprehensive annual botanical reports about the work of the Botanic and Afforestation Department, detailing progress with planting the colony. The beautifully written reports can be read today on the Hong Kong Government Reports Online (http://sunzi.lib.hku.hk/hkgro/).)

INTERVIEWER: Good morning listeners, I’m speaking to you from the Hong Kong Herbarium in Government Gardens in the heart of the City of Victoria. And I have come to this place to interview Mr Charles Ford, the Superintendent of Hong Kong’s Government Gardens and Tree Planting Department.

I have been sparsely furnished with details of Mr Ford’s life, but I do know that Mr Ford has a background in botany and horticulture, and that he came to Hong Kong from Kew Royal Botanic Gardens in London to work on a project of forestation and park development here in our remote colony. While a resident in the colony from 1871, Mr Ford has founded the Hong Kong Herbarium of dried plants, the first public herbarium in China, and he leads the ambitious forestation programme which has transformed the hills of Hong Kong Island from an unseemly rocky and barren terrain to the hills that we see today covered in lush vegetation and offering a prospect most pleasing to the eye.

I have talked to some people that have worked closely with Mr Ford and they characterize him as a deeply serious and committed civil servant, somewhat opinionated at times. Mr Ford receives considerable admiration for his work, even if he does not always win sympathy. All I can say is that I am pleased that he has cordially agreed to have a conversation with us today about his work and life in Hong Kong.

On this morning it rains exceedingly and I know that Mr Ford has been out to oversee planting work on the Peak. Oh! but here he comes now... A tall and distinguished-looking gentleman with fully grown, well-groomed beard and a fine moustache. He walks towards us with an air of gravity and majesty, and he walks slowly, very slowly, as if moving in a denser atmosphere from the rest of us.

INTERVIEWER: It is a very great pleasure to meet you Mr Ford, and thank you for agreeing to talk to us today. Could you perhaps start by telling us what you are working on at the moment, and where you have been this morning?

MR FORD: Well, to put it plainly, around our dwellings are forested hillsides, but this is not a place where forests exist naturally, so it is, to a degree, artificial, composed of various introduced natural objects. At the moment, we are in the midst of a highly ambitious and challenging project of planting the hills overlooking the City and Harbour here on Hong Kong Island. We nurture fresh vegetation in its bristling infancy and we cut down mature vegetation so it does not grow too exuberantly. This, to be true, is labour intensive work. Besides costing large sums of money, it requires endless labour and natural resources to water and fertilize the hills. To this end, I have to train and supervise our forest staff and local coolies, who move between our government tree nurseries, where they collect, dry, and grow seeds, and the hills to which we transplant select species of plants, which we then plant, prune, thin, water, and fertilize; all to ensure a uniform green expanse on our Island. In the seven years since my appointment in 1871, just over 77.000 trees have been planted.

INTERVIEWER: Mr Ford, I would like you to speak in more detail about this project of forestation and the process of selecting the right species to plant here. But before that, can you tell us a little bit about your background – your past and where you come from?

MR FORD: Let’s see, I was born in King’s Lynn, in Norfolk in East Anglia, where ungenial climate wraps the hedge-rows and the hill-farms in mist and driving sleet. I went down to London to study botany and horticulture, and after that I found employment with the Herbarium in the Royal Gardens in Kew. Apart from that… well, my life was uneventful enough, as far as events go. And I find that memory consists to large degree in the recall of past torments. I had a wife and then I lost a wife and we did not have children – I am trained in botany but I cannot brag of my own fertility! (dry laughter) Later when I was offered the position of Superintendent of Government Gardens here in Hong Kong, I knew this was an opportunity to implement in this far corner of empire the proudest British traditions of horticulture and botanic study.

INTERVIEWER: And how do you find your life here in Hong Kong, having now spent around seven years in the colony?

MR FORD: But actually, my attention is focused singularly on my work and study here, as indeed it should be, and my motions at present are highly limited. I move much like a pendulum or an oscillatory – I swing from home, to my office and laboratory in Victoria, to the plantation station and then out on the hills to supervise work. Hong Kong affords very little agreeable company for me so my time I spend mostly with myself, my head in my books, and articles, and my writing.

I do like to amuse myself with the new wooden jigsaw puzzles which I have sent here from England each month. Doing these puzzles is a very restful exercise for me and a way of regaining composure away from the frenzied and congested world in which I find myself. I suppose that I enjoy going inwards and not talking to another person for hours. Soon science will prove beyond all reasonable doubt, I venture to believe, that the silent, focused pastime of the jigsaw puzzle can prevent neurasthenia, heart attack, and gastric ulcer.

INTERVIEWER: Well, it sounds a bit lonely, Mr Ford. Surely there are social circles here you seek or people whom you befriend?

MR FORD: As for female company, I am not interested in the vulgar romances that run into a few days or weeks, and distract me from my work here. This I would never permit. I hardly ever go out, and not for want of being asked. Once people come to the understanding that such is my habit, I find myself welcomed exceedingly when I do go out, which is always without announcing my intention of doing so. I suspect that I am regarded as somewhat of a recluse and perhaps a sulky one at that, but I am not unkind and I am also not wholly unpleasant to myself. I like to work very late at night, and sometimes through the night if there is much work on hand.

INTERVIEWER: I understand. But what about the many traders and merchants resident in the colony, do you sometimes socialize with them?

MR FORD: Listen, I have learned the history of Hong Kong and I am aware that HK, from its foundation a little more than three decades ago, was an imperfectly conceived colony, a mere product of cynical opportunism and little else, acquired by us, the British, in the most dubious of colonial wars, as a key to vast new markets. Our city was born from the rocks and it began as an off-shore entrepôt where merchants could store and trade opium unimpeded by Chinese officials. To extract wealth out of the bowels of the land was the desire of the first commercial settlers; there was no moral purpose behind them, no higher principle – no more than is in a burglar breaking into a safe. And you ask me about the merchants resident here. I will not walk with them. They walk everywhere with their concubines or compradors, or rather with their concubines and compradors. There is not an atom of dignity in the whole batch of them. Their salaries consist in bribes and unjust exactions and, look at them, almost all of them grow stout before their time; they are all portly men at the age of forty with graying hair, their coats are dusty and they are slovenly and negligent in their habits. Have you not noticed that?

INTERVIEWER: (hesitantly) Right, well… I suppose I have noticed that.

MR FORD: As far as I can tell, merchants are absent-minded in anything but money matters. And absent-mindedness has a charm only for thoughtful men, where it means deliberate abstraction and an aloofness from ordinary sublunary affairs. You must understand that.

INTERVIEWER: (laughing) Well said, Sir!

MR FORD: On another note, every time I walk by the Harbour and the Queen’s Pier, I see soldiers and sailors in great numbers disembarking their ships and unleashed in the streets here. To tell you the truth, it disgusts me as much as anything human can disgust me. Simple, rudimentary souls that flock to drinking parlours, opium dens, and brothels. Everywhere are ignorant and uncouth people; they are irretrievably frivolous and prefer arousal to contemplation, reflection, or decent work. Hong Kong, as is clear for all to see, is truly the bordello of the Far East, and of all the innumerable ladies of pleasure that are in Asia, those found in China must be, by far, the most numerous and affordable.

INTERVIEWER: Mr Ford, you have strong views on these matters, clearly based on years already spent in this colony, but I prefer it if we can avoid any statements that may cause offence to our listeners…

MR FORD: Well, the facts themselves, or rather the facts in combination, tell us that Hong Kong is a magnet for the unpleasing types of which humanity affords such numerous instances. This is the remotest corner of empire, and the pinnacle of sordidness, with an unsavory reputation for vice and crime. And the native men here – a foreign, undeveloped, mysterious people – sit around in their repulsive state of slovenliness, or they gamble their savings away, or, worst of all, they enter the Chinese bazaar in abundant numbers, where they end up in opium dens as human wrecks, pale ghosts, rapt in the phantasmagoria of their opium dreams; these reclining ghosts have their lips glued to the opium pipe, all the while their neglected children, the inheritors of their parents’ misfortune, sit alone with their nutritional edemas and deficiency symptoms. No, we, the British, come to these foreign shores to benefit the natives. Truly. Hong Kong did not begin well, but now we can say that, through our efforts here, education is promoted, laws and governments are instituted, hostile conflicts are prevented, the oppressed are protected, the enslaved liberated, and the hills are forested in the most expedient way possible. Finally, we may say that our presence here is a civilizing mission to benefit the lower race!

INTERVIEWER: (indignantly) Mr Ford, enough on that matter, if you don’t mind! Again, we should not cause offence to our listeners. I hope you will allow me to explain a little to our listeners now… Mr Ford is clearly a man of his age, espousing opinions not all of which we might wish to confide to posterity. It is unavoidable that some of the views expressed in this interview perpetuate the old habits of western superiority, hardened over the years into a habitual insolence. We might even characterize such opinion as the dead weight of an intolerant tradition that prevents understanding and real exchange between peoples…

MR FORD: (suddenly rigid, surprisingly alert, speaking sharply) That’s what you say. It’s not what I say! Why ask questions, young man, if you cannot bear to hear the answers?

INTERVIEWER: Well, you’re voicing a valid objection here, Mr Ford. But surely those that you have just characterized as an undeveloped, mysterious people are our fellow human beings here in Hong Kong, and not some nebulous collective of aliens.

MR FORD: The idea that all men are the same and equal is fundamentally mistaken and disastrous. That is all there is to say on the matter.

INTERVIEWER: I understand your position, I do. But now let us turn to the subject, a less contentious one I expect, of the nature and significance of the ongoing project of forestation. How would you explain to our listeners the importance of the work you and your staff perform here on Hong Kong Island presently?

MR FORD: The importance of our work is a serious and weighty subject. But let me first offer you a few preliminaries if I may?

INTERVIEWER: Certainly, by all means.

MR FORD: Prior to 1872, when I was appointed to the position of Superintendent of Government Gardens and Tree Planting, and J. M. Price became Surveyor General, planting in Hong Kong was mainly done in a few gardens and alongside main roads and avenues. Banyan trees, Indian rubber trees, and bamboos were chiefly used then, and notwithstanding the exposed situation of the trees they have grown well and are mostly in a healthy state today. Planting began in earnest in 1873, from which year we decided to plant mostly the native China fir (the pinus sinensis) – the extremely graceful evergreen conifer so admirably adapted for propagation in the Hong Kong hills from its ability to thrive in the most exposed places and the poorest of soils. Before that, the bastard banyan – the ficus retusa, a remarkable and majestic growth – was almost exclusively used. It takes roots easily and requires little attention and care in its rearing and it began gradually to cover the baldness of the hills. But now we understand the considerable damage that accrues to sewers, pavements, and foundations of house-walls by the banyan’s long straggling surface roots, which travel to great distances in search of moisture, and insinuate themselves between the joints of stones which they eventually upheave. Our work requires a judicious selection of hardy classes of plants, and I correspond regularly with my colleagues in Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, and botanic gardens in Singapore, Melbourne, and Calcutta to select the best stock of trees agreeable to the nature of the soil and situation in this part of the world where typhoons are so prevalent and the exposure is so great. At the present moment we plant the China fir, the red Australian cedar, Indian rubbers, the bombax, cocoanut palms, and camphor trees, while numerous other plants are grown experimentally with the object of testing their adaptability to the climate and soil. As I mentioned before, a little more than 77.000 trees have been planted since 1873, but I acknowledge that the result today is somewhat disheartening: vegetation dots a few streets and suburban roads and a ravine or two of Victoria Peak, as well as some patches on the hills that overlook the harbor. But here the scattered forestation serves only to remind us more painfully of the glaring bareness of the surrounding hills. We need to change that.

Truly, we have a herculean task ahead of us. We plant on the hillsides that are exposed to the North-East monsoon and to the action of typhoons, and here it is requisite to plant thickly to enable trees to shelter one another. I calculate approximately 1740 trees to the acre, and with the over 10.000 acres that ought to be planted, we are looking at over 17 million trees. At the tortoise speed of our current operation it would take us over 1000 years to complete the job – a circumstance sufficiently mortifying. The search for larger and suitable nursery sites should begin promptly to enable us to plant upwards of one million trees per annum, this is imperative, and we need much larger numbers of coolies. But even so, the obstacles to our operation are phenomenal.

INTERVIEWER: And can you just explain to us what some of the main challenges to this ambitious programme of forestation are?

MR FORD: Well, briefly put, the impact of typhoons and landslides is devastating. Frequent scourges of herbivorous caterpillars destroy our plants, while the locals come up here to carry out illegal logging for timber and firewood on a vast scale, and we have not the staff required to patrol the many paths that run through the forested areas. In addition to that, fires break out regularly, caused mostly by locals who come to burn incense at the many ancestor’s tombs scattered around the hillsides.

INTERVIEWER: Mr Ford, you have founded the herbarium of dried plants here in Hong Kong’s Government Gardens and you have supervised the construction of the Orchid House in the same location. Both are recognized as important institutions for advancing our study of botany in the Far East. Also you publish articles based on your work and study here in the colony and you produce, if I may say so, beautifully written and highly detailed annual reports about the work of, as you put it in one of your reports, “clothing the naked granite in arborescent vegetation”. Can you talk to us about how important scholarly study and writing is in this work you are carrying out?

In our work we must indulge in a vast scheme and study that requires minute and accurate investigation. This means not only reading forestry manuals and scientifical articles, but also collating and interpreting data, always with precise nomenclature and classification of botanic specimens. You ask me about writing and you say pleasing things about my annual reports, but you must understand that forestation, tree planting, is my real and most important composition, my oeuvre. I believe that we have an obligation in life to leave some traces of our journey behind us – to leave something behind of lasting value so we do not go unrecorded into the grave, and in our written records we must never allow ourselves to be careless in form or obscure in expression. Trust has been placed in us to plant the territory, and this task we must pursue with absolute integrity and commitment.

My assistants observe me as I sit crouched on the ground and select the right spot to plant a seed, the right way to put it into the ground. I release the seed into the ground with a gentle, curving movement of the hand (making a gentle, curving movement of his hand) to make sure it clings to the ground and puts down its roots. In this work we have to understand the seed, grasp the entire plant, before we release it into the ground, to ensure that fresh vegetation is in the right place, and will not be washed away by the rain or half-smothered by an aggressive neighbor or by harmful, insidious grasses – we must never permit a lawless, utterly rustic jungle.

INTERVIEWER: I understand that if one begins to examine this apparently uninteresting subject in some depth, one will find that quite a lot can be said about it which is not at all uninteresting. You certainly demonstrate that, Mr Ford. So, here we have the perspective of one of England’s preeminent horticulturalists on what has to be the often painstaking, monotonous work of planting…

MR FORD: (clearly upset, speaking in a loud voice) Monotonous? NO! You must not trivialize our work. never make it trivial! This is scientifical work. Look, in science we must establish for our every action a limited and precise object; our taste ought to be for the particular, the individual, the characteristic. And so in forestation we take a sample area, a small, manageable square section, say one square meter, and within this we ensure an ideal distribution of species, that is to say, an ideal ratio of native and introduced species. We comprehend their interaction, consider the number of leaves and the direction of their growth. We calculate their precise distribution, and then, armed with this comprehensive, statistical understanding, we can move on to another, extended section and ensure full consistency in all respects. Training our gaze to examine distinct objects with neutral objectivity is a key to mastering the world’s complexity.

INTERVIEWER: Mr Ford, this is truly enlightening and I feel like exclaiming “YES! It is like this!” But listening to you calls forth further questions. And so, please permit me to probe this a little further if I may? In my capacity as a layman, of course.

MR FORD: Naturally.

INTERVIEWER: How is what you say here practically possible when all is growing? Plants merge and become nourishment for each other. Seeds and pollen fly through the air and should perhaps not be counted. Can we ever really calculate the number of leaves when plants extend and their roots travel underground. Some growths have withered, while others sprout spontaneously or will sprout the next moment; what should be counted when nothing obeys distinct borders in this realm? Each time – at each stage – we’re confronted with variance and multiplication, flux and chaotic proliferation. Where and when to start counting and when to stop?

MR FORD: Quite right! A forest is a collection of growths – it grows. And that is how the problem must be formulated. We work with cultivated species and subspecies or subcollections of growths, and there is an intersection between those, the boundary of which cannot be clearly defined, and so it remains partly indistinguishable. In truth, we never really notice individual growths, the individual little plants; instead we see a cultivated area, a forest. But the trained botanist sees both dimensions; he sees the forest, an organic whole, and he sees its constituent parts, the multitude of individual, distinct species. Ultimately, a botanist moves beyond numbering growths and grasping individualities; instead, he becomes able to grasp it all intuitively – in other words, to grasp all in one glance. This, of course, is only possible after years of training and hard work in all dimensions. Such is the case when we study a square meter of cultivation, or the entire cosmos – at once we are confronted with order and random multiplication. This is how we should come to see it, and then we should go no further than that. If we explore things much further they become difficult to determine and we enter a realm of the ineffable.

INTERVIEWER: Fascinating! Mr Ford, you’re talking about how we, in order to be accomplished in a discipline – in any discipline in fact – have to limit our field of observation and keep our sensations and impressions under control insofar as possible. On the basis of the rationale you have outlined, the people of Hong Kong are now beginning to appreciate the beauty of the hillsides: We walk on paths through forested areas where many birds sing, and we notice how the odour of lush vegetation and blossoming flowers intoxicates the air.

MR FORD (frowning): This is partly true. But what you state here is also, if you don’t mind my saying so, an unenlightened, retrograde position, and that in spite of all I have just said. Listen, our work is about so much more than offering a pleasant recreational terrain of flowers and green canopies. In any case, nature appreciation –

the taste for natural scenery – is not yet universal in our world. But it will be one day, of that I have no doubt. One day all will love the woods and hills for themselves and gaze on nature with some reverent awe, and then our work will be unanimously regarded as of the highest importance and as essential to our well-being. No, our effort at forestation is a moral obligation, it is a civilizing mission. It is a truth universally acknowledged that the improved health of a colony is in great measure due to our efforts to transform wild and craggy rocks into a benign, verdant land.

In the first decades of the colony, our hills looked akin to a lunar landscape, with their dark, rugged terrain strewn with rock fragments and erratic boulders. Just look at the old pictures! For that reason the earliest written accounts we have of Hong Kong Island, penned by western residents and visitors, invariably refer to it as a barren rock, a barren, rugged island, or some similar description. Indeed, the cliffs looked ominous to the early residents who inhabited a narrow rim of rocky land perched precariously between cliffs and sea. When our predecessors scaled the naked summit of the Island and observed the terrain around them they must have thought that they inhabited fragments of land seemingly disjointed from the continent by some sudden and violent convulsion of nature. It was exceedingly difficult for the early settlers to imagine a settlement of residences, warehouses, and offices in this rocky and inhospitable terrain. They averted their eyes from the rocky Peak; only a few of them looked up at the Peak and then they felt they were staring into the black, scaly back of a mighty dormant dragon, which could awake from its slumber any moment, shake the houses off like ashes scattered to the wind, and, with one fabulous gesture, dip its head into the water to assuage itself.

Forestation is a moral obligation – we have a moral responsibility to cultivate and make beautiful the primitive terrain that surrounds us as our colony becomes extensive and prosperous. This is civilizing – it is a societal good: It is to do the good work. This is our holy mission (said with a wry smile)!

INTERVIEWER: (Somewhat taken aback by Mr Ford’s final statement) A holy mission? And forestation as a moral imperative, Mr Ford? You make it sound like a spiritual engagement. Are you a religious man, Sir?

MR FORD: Well, if there is a God, he will speak many languages, and botany, understood as the study and cultivation of the richness of nature, is sure to be one of them. But religious sacredness is not the way life presents itself to me. And, to be frank, I have always regarded religion with a practical indifference. Of prayer and worship I know practically nothing. So, I am not really a practicing Christian, but I also have no desire to tilt against religious orthodoxies and accepted dogmas, and I certainly have no contemptuous hatred of theology and of creeds. Like most people I yearn for strength and serenity, and I find more than just a medicine in botany. As you can tell, I am safely anchored in our natural world. If you ask me what I believe in, I answer you that I believe in forestation. It is what I am put here to promote and I pursue it with devotion and scrupulous tenacity. Mine is, you might say, a temperate and rational faith.