Walking is Healing

(written October 2018)

“It looks good, we’re on target”; these were the reassuring words spoken by my doctor that Tuesday morning in small a nondescript consultation room in the Department of Surgery of Hong Kong's Queen Mary Hospital on one of my weekly check-ups following my six-week stay and operation for heart disease in the Sun Yat-Sen Cardiovascular Hospital located in the Nanshan district of Shenzhen to the north of the Hong Kong territory. The statement referred to the result of a blood test taken earlier that morning, and specifically to the index for blood coagulation. Ever since my operation one month previously I had been dutifully ingesting a dose of small blood-thinning tablets to secure a smooth, un-clotted flow of blood through the brand new mechanical heart valves that had been installed in my operation. I could now look forward to taking these pills till the end of my days.

Looking back, indications that something was wrong began to occur about seven months before this Tuesday morning, when I started to experience unusual fatigue, a loss of appetite, and a consequent plummeting of my weight which meant I lost about one fourth of my body mass. Also I had developed fever in the evening tide as well as frequent night sweats, which were hard to account for as we were going through the coolest months in the year, and this year they were unusually cold.This situation worsened progressively as I went for months happily, and stupidly, ignoring these alarming symptoms. That is until one day, at the end of April, when I was invited up to Shenzhen to work as a judge in an English speech contest. My wife had chosen to accompany me that day, and at the end of the event, during which I had struggled to sit erect and keep my focus through 21 well-crafted but hardly inspired speeches, and everyone I knew had exclaimed ‘Wow! You’re so thin!’, she pushed me into a taxi and demanded to be taken to the Shenzhen branch of the Hong Kong University Hospital to learn the reason for my manifest, and now very public, demise.

Gram Positive

In the hospital I was admitted into the respiratory department, and the following morning we knew exactly what the problem was. A blood culture had shown a systemic infection with bacteria in my bloodstream. The culprit, it was determined, was the bacterium gram positive, a rod-shaped bacterium that appears, strikingly and unmistakably, purple-coloured when observed through a microscope; The bacterium was named after the Danish bacteriologist Hans Christian Joachim Gram (1853-1938), a professor of medicine at the University of Copenhagen, who as several biographers have pointed out was an exceptionally modest man (he opened his initial publication with the words “I have published the method, although I am aware that as yet it is very defective and imperfect; but it is hoped that also in the hands of other investigators it will turn out to be useful.”), and who proceeded by examinations so detailed and meticulous that they caused his students and assistants to lose patience with him, though they all had nothing but the highest respect for his principle of thorough clinical grounding. Professor Gram pioneered a now standard method for staining and classifying types of bacteria, and as the crown of his illustrious medical career he had this tiny bacterium named after him that was now rushing through my veins. A subsequent ultrasound scan revealed that the gram bacteria had settled as an accretion of bacterial matter on the inner surface of the heart, where it had already wreaked an inordinate amount of damage to the heart valves. I recall looking, shocked and incredulous, at the doctor’s ultrasound recording, that showed the growth, what the doctor termed a vegetation, which most resembled a broccoli with an elongated stem, being tossed hither and thither as the diligent heart valve dutifully went about its work of enabling the flow of blood through the heart and preventing backflow, seemingly oblivious of the alien growth that had planted itself on top of it. As I sat looking at the ominous black and white recording of the dancing vegetation I was amazed that it could stay attached, and I was at least open to the argument, put forward by several doctors in the days that followed, that it might not for much longer, and that to have it enter the bloodstream and very possibly block the aorta or lodge in the brain could prove enormously counterproductive.

I remember returning from the ultrasound department to my room in the respiratory ward when a young female doctor met for the first time approached me and, completely unbidden and without introducing herself first, had the audacity to utter the words, which of course turned out to be entirely accurate, but which nonetheless sent a chill down my spine, that my heart was badly damaged and I would probably need heart surgery. At that moment, the statement seemed to me frivolous, unnecessarily theatrical, and quite frankly in poor taste. Who was this individual to blatantly convey to me such a dismal message and with what authority? I was still naively hopeful that a treatment – a major bombardment – with antibiotics might eradicate the bacterial growth. Well, naïve perhaps, but dreams cost nothing. I was immediately transferred to the cardiac department of the Hong Kong Hospital, conveniently located on the floor above respiratory, where the doctor said they would recommend surgery but also that I transfer to the Sun Yat-Sen Cardiovascular Hospital in Nanshan district where they had better expertise to perform the heart surgery required.

That same evening, having been transferred by ambulance to the Sun Yat-Sen hospital and admitted into my room and duly changed into the blue-striped hospital clothes that are an almost exact replica of the garments worn by the inmates of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp during the Holocaust, clearly a timeless design, I found myself in a new bed, looking up at a team of doctors, led by doctors Wei and Wang with their junior following. On the side of my bed stood my wife and now also my sister, who without a moment’s hesitation and on the advice of her doctor friend (“you need to pack your suitcase now! Your brother needs you.”) had booked a flight ticket the previous day from Copenhagen to Hong Kong. The message from the team was clear and unmistakable. First, that they had studied the result of ultrasound examination and MRI scans and concluded that an operation was not just absolutely necessary but also urgent. Second, that my condition is known as infective endocarditis, and that it came with a 25% risk of death, which increased to a full 100% if left untreated. And, third, that I would have to decide if I wanted organic or mechanical heart valves inserted. Infective endocarditis… infective endocarditis… Dr Wei pronounced the term with such breath-taking rapidity it suggested to me it was a term of medical jargon they threw about every day. When I tried to pronounce it with my untrained tongue, it would never come out right. Naturally we were taken aback by these announcements. For one thing, I had a deficit of trust in Chinese hospitals; up to this point I had generally found that it’s easier to be prejudiced against Chinese doctors because it saves you the trouble of having to make up your mind each time you meet one. Open heart surgery conducted in a Chinese hospital was not high up on my wish list; in fact, it was not even on it at all. And how could we possibly make a qualified decision on the matter of mechanical heart valves versus organic ones, which I assumed would be taken from pigs. What further complicated this last question was that I, admittedly a person of very few principles, had at least two principles that I had managed to stick to with some consistency up to this moment, and these now caused me some perplexity. The first was to have as few metal objects as possible absorbed into my body, and the second was to cut down on my consumption of meat, notably pork. But on the other hand, my odds if I decided not to undergo treatment seemed decidedly unattractive. Both my wife and my sister, the latter jetlagged and entirely out of her comfort zone, managed to keep a calm head and consulted their contacts in the medical world; the message received from Denmark corroborated what was already said by the Chinese doctors; heart surgery was indeed necessary and it would probably be smartest to have it done in China (‘actually in China they have gotten quite good at these sort of things.’). At hourly intervals the doctors returned to my room to ask if I had made up my mind; pressure was on! My first inclination was to return to my home country to have the operation done, close to my family, in a place with noted excellence in heart surgery and where communication with hospital staff would be easy and uncomplicated, but this possibility was dismissed by doctors Wei and Wang with a synchronised shaking of their heads and overbearing smiles: A 10-12 hour long-haul flight inside a pressurised cabin was not what I needed at this stage, they would simply not allow it. Suddenly one image which I must have kept in some compartment of my memory flashed by; as a young boy I once travelled in a holiday with my parents to London and I took a sip of my bottled water at cruising altitude, then put the cap back on and sealed the plastic bottle; it had crushed and crumbled on descent as our aeroplane approached sea level. Figuring that the same principles of reduced atmospheric pressure might apply to my own body at some level, so to speak, I was prepared to accept the position that flying was a bad idea. The doctors also ruled out, gently but firmly and, this time the entire team of doctors with the same synchronised shaking of the head, the possibility that the antibiotic treatment I had already started in Hong Kong University Hospital might successfully work to eradicate the bacterial growth. So, the decision was made to have the procedure done, the requisite consent forms were completed with a request for mechanical heart valves, which the doctors ensured me would be good for the next approximately fifty years of my life, as opposed to the fifteen years of the organic valves. The nurse who instructed us in this stage of the procedure noted my obvious apprehension and remarked ‘Don’t worry. The doctors do this all the time’, a remark which, when viewed in a certain light was a positive statement, and one obviously intended to calm my nerves, which it did. The operation was scheduled for 8 am the following day, a Monday morning.

Mortal Awareness

Thus for the first time in my life I felt that I had been visited by my own mortality. According to the leading Dr Wei my case of infective endocarditis was categorised as a heart failure, which of course sounded alarming enough, though I had to assume that, as a diagnostic term, ‘heart failure’ comprised a scale, at the end stage of which would be a failed heard, i.e. a heart that had stopped pumping blood, which clearly and demonstrably was not the point we were at. “you may die from this”, was the matter-of-fact statement which made complete sense to my objective understanding: I could study the results of my various examinations and note that objectively things looked awry, I could fact-check my condition online, read about the mortality rate and the surgical procedure that awaited me. But this objective or theoretical understanding was not where I resided. To my subjective awareness, however, the doctors’ worrying pronouncements were unnecessarily alarmist and really rather bothersome. Above all, they seemed to me irrelevant for I still could not feel I was in any imminent danger. The communications from doctors to me and wife and sister were understood but they continued to feel like they didn't relate to me directly. Whatever Latin jargon was served up by the doctors was all taken cum grano salis. My heart pumped strongly, I had seen it, in fact I had found the sight quite touching of my own dear heart valves diligently carrying out their work, while providing a platform for a surreal dancing vegetation. The heart is a resilient muscular organ; it gets on with it! One cannot feel a vulgar and nonsentient bacterial growth upon the heart. Even if my life was in some degree of danger, I certainly could not feel it. I lived entirely in this subjective space of understanding, or more accurately of disbelief.

I speculated that even if the clump of bacteria had suddenly detached itself from the heart and was being rushed around the cardiovascular system I probably would not have felt anything, and death might have been sudden and painless. Perhaps. And perhaps it would not be the worst way to go; similar maybe to a person dying from a stroke or a pulmonary embolism while enjoying a comedy on TV, while bending over to collect droppings from one’s dog while out for a walk, or while sitting down to organise a stamp collection. Or similar, I thought, to a life being extinguished suddenly by a lightning that strikes from above. Much later, as I was flipping through old newspapers, I discovered that this was precisely what happened to a young man who died in Hong Kong the very same Monday that I was operated on in Shenzhen, a rainy and dismal day. At 12.45 pm, about an hour after my operation was completed, and at the moment when I was transported from the operating theatre to the intensive care unit of the Sun Yat-Sen Hospital where I was slowly regaining my senses as I emerged from general anesthesia, an 18-year-old recent graduate from the South Island School in Aberdeen on Hong Kong Island, while hiking with six friends along a section of the MacLehose Trail in the beautiful Ma On Shan Country Park, was struck by an enormous electric current from one of the 568 lightning strikes that were reported between noon and 1 pm in a thunderstorm over the eastern New Territories. Unconscious and not breathing, he was flown by helicopter to the Pamela Youde Hospital, where attempts to resuscitate him failed and he was declared dead at 2.15 pm, while I was asleep. Did this man, I wondered, have a premonition of his own death? Was he somehow aware that the ground beneath his feet was about to split open as he sat down that morning, an entirely ordinary morning and ate an entirely ordinary breakfast? Death, I understand, can sometimes give advance warning of its arrival, and so maybe he knew or sensed that his brief light was almost spent, this young individual released into history for all too brief a spell.

Being an amateur of my own life I have always been spectacularly unreflective, unphilosophical one might say, on the subject of death. I suppose I have always believed that I would come to mortal awareness at some stage, that to do so is part of maturing, perhaps at a time when death draws nigh or when (or if) I begin to fear it, perhaps at a time when my future feels like it has been over a long time ago and it is too late to start over. Or maybe, being in the mid-40s, where I am now, is probably when you should begin to think of death, at a time when, with a tiny bit of luck, you have as much left of life as you have devoured. I have so far felt the subject’s utter irrelevance to me; that when I’m here, death isn’t, and when death is here, I’m not. In other words, that the two domains will not coincide, and have never coincided, except for the two instances in my life where I had seen, and touched, a dead person. This being said, I suppose I have had two assumptions about death, both unsurprising to most I expect, for as long back as I can recall. The first is that I will die one day and that my days are limited. I believe my own death to be statistically probable and that it will have a specific time and date. One day, a paper will exist in the world with the heading ‘Death Certificate’, it will have my name on it and it will record that specific time and date when I departed, and probably the cause. This document will be part of a standard procedure of bookkeeping, pure protocol, the absolute regularization of death. Once I had managed to get over this minor speed bump in the road, across which a doctor has written (in barely legible handwriting) the words ‘infective endocarditis’, I will once again continue along life’s highway at the astonishing speed of four thousand four hundred heart beats per hour, destined for my own finality. My other assumption is that this finality, death commonly called, will involve the most extraordinary changes to myself and to those close to me, but also that those changes will be of fundamentally different orders: for those close to me they will be in the form of the practical and emotional changes that stem from not having me around any more, and these can be said to not concern me in any direct way. For myself, on death’s receiving end, so to speak, there will occur a series of well-described physiological changes, a number of them observable, that include, for instance, paralysis, stiffness, lividity, that is the visible reddish marks as blood settles in the lover parts of the body, the absolute and irrevocable extinction of cognitive faculties, and the permanent absence of sensation and awareness. Death would entail cessation of all my pains, it would mean being rid of everything, most significantly of myself; then I and nothing will have become one. I can only hope that, at that time, death and I will have no unfinished business and that we will have arrived at an agreement that is mutually advantageous for us both. Among the facile maxims on the subject of death of which I know of no confirmation, is the postulate that we will find out what death is like eventually, or ‘soon enough’, when we cross over for good. I suspect that we will never find out because we are unlikely to possess the cognitive faculties through which to receive any such enlightenment; all we can use to understand the brain and consciousness are the brain and consciousness itself, and when these are irrevocably extinguished then what enlightenment can there possibly be? Another seemingly reliable saying that I was never able to say with any conviction though I suspect I may have reiterated it at some point, is the argument that if one is earnest in one’s fear of death, understood essentially as a fear of non-existence, one ought be equally fearful of the time that precedes one’s birth, or, to put it otherwise, that the immense prenatal void out of which one has emerged ought to provoke terror the moment one realises that one did not exist in it at all and that no one appears to mourn one’s absence. I could never grasp this postulate subjectively, and always suspected that the argument contains a fallacious reasoning of some sort which a person with greater philosophical aptitude than I would be able to demonstrate relatively effortlessly.

Oh, how we surround ourselves with statements and thoughts on the subject of death that make tremendous sense in matters of the emotions, one such being the idea that the dead are watching over the living, which I must admit I have previously found a most comforting thought and one that does not strike me at all as spooky. In reality, I cannot entertain even the most timid hope for a disembodied spiritual afterlife, and at the same time death does not, can never fill me with fear. What does fill me with absolute fear; a fear which I have recently come to suspect goes beyond that of most average people, and which has only increased as I got older, is a fear of how ageing may affect us and especially of a long drawn-out senility, which I once heard someone describe chillingly as living with a terrorist inside the brain. Senile dementia, frontotemporal dementia, Parkinson’s disease dementia, Lewy body dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Creutzfeld-Jacobs disease: these are sufferings that come to haunt me in my nightmares and together they resound as a litany of horrors, a horror of the methodically eroding identity, the horror of everyday skills slowly unlearning themselves, of motor skills gone awry, and of the loss of memory and lucidity which also betokens a loss of identity, all the while that little corner of our brain remains lucid enough to feel the appalling and acute horror of it all, feeling painfully aware that something is hopelessly, irrevocably wrong, that the progress towards disappearance for ever has begun, as it registers the sadness printed in the faces of loved ones who listen to one’s confused and demented confabulations. The highest pitch of agony and horror.

Writing and Death

If I was a praying man, I would ask God not to call me to his heavenly flock any time soon and certainly not on account of some tiny, vulgar bacteria clump. At the very least I should desire to witness the expiry of my passport and visa card, preferably in a comparatively lucid state of mind, and, ideally, also to be able to read and write a lot more than I have so far, perhaps even write another book. Do we write to defy death? Is writing a race against time? These were questions that I had pondered in the past, and never more so than these last few days after my diagnosis. A few years ago when I had published two books, specialised academic books in literary and religious studies – the sort of books that were never, could never become, a commercial success – I confess I did enjoy searching for my books in library catalogues, deriving some moderate degree of pleasure, some comfort I suppose, from locating my titles in institutional libraries such as the New York Public Library (where a part of the research for one book was carried out), the Library of Congress, Queen’s University Belfast (two copies of each book, as I recall), Göttingen University Library, the Royal Library in Copenhagen, the John Rylands Library of Manchester University, and the university libraries of fabled institutes of higher learning such as Cambridge, Harvard, and Stanford. The technical term for this sort of behaviour is ‘narcissism’, which is frowned upon in some circles and may in some cases qualify as a personality disorder, but now I wondered if it also had to do with an awareness of death, and specifically with looking for some form of consolation or redemption in the face of our impending annihilation. Books are a way of saying ‘I was here’. They are the particles, for which I was the first mover, that are now disseminated around the world, like ashes scattered to the wind. In any case, and if nothing else, my modest oeuvre takes up space – it occupies concrete, material space – in these institutions which I know and admire, institutions that are in part tasked with the safekeeping of its written materials. My thinking has, in other words, become institutionalised; to put it bluntly and less optimistically, it has been condemned to mass confinement alongside all that other stuff that gets churned out from our academic assembly lines – scholarly chaff ground out in our academic publishing factories – weighty tomes that bend down the shelves on which they stand with their heavy ballast of scholarly apparatus and references and never-ending elucidation. I can only hope that some reader in the future may browse through these humble pages of mine, and encounter ideas and phrasings thought out so long ago: the bound book is like a vault in which is preserved evidence of some degree of lucid thinking and of my interests and experiences of absorbed productivity at a certain moment in time. Yet, as I thought about this in the cardiac surgery ward, and as my mind succumbed to some negativity and discouragement at this testing moment, I also had an acute feeling of the utter insufficiency of these books, not just mine, and how precious few insights they contain that can be said to be truly luminous. Instead of luminous insights we find constant speculation and theorisation about meanings. In truth, my books, precisely like its many ‘shelfmates’ locked up in their mass confinement where they gather layers of dust and mould, are for the chief part, but to varying degrees, derivative and unconvincing. As dull and uninspired as doctoral theses, these abundant books, that we often group, tellingly, as secondary works, shrivel down to only a very few worthy ideas, a handful at best. In fact, it would really suffice to read and study those few ideas that may come in the form of a few apt and appropriate words or sentences that penetrate to the core of the subject matter. We may skip the circumlocutions and go straight to a distilled argumentative core. In its consequence this would make authors like me writers of aphorisms, what the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard disparagingly but accurately characterised as ‘calendar philosophers, practising the minor art of the intellectual asthma, whose sayings find their way onto the walls of dentist’s waiting rooms’. But we tend not to publish merely a sentence or two, although we know perfectly well that this would save precious natural resources, as well as readers an enormous amount of time that they could direct towards more worthwhile endeavours. Publishers, and their customers, expect books to be book-length; this means more often than not, I thought, that the writer has to allude to theory, that he needs to position himself (and does so often routinely and unenthusiastically) in relation to other studies in the field or to reigning theoretical paradigms. A writer is encouraged to extrapolate as much and as far as possible from a very tiny arsenal of ideas. Just as a book is wrapped in protective hard covers, so once we open that book we find that the few ideas contained within it that can be said to be truly useful are wrapped in layers of repellent and redundant verbiage. It is futile to expect great effects from tiny ideas. And whatever useful ideas are there, it struck me, are far more likely to be misunderstood – or to be ignored and unappreciated – than they are likely to be understood correctly.

One of my books, I now recalled, was reviewed by a British historian in the Times Literary Supplement and the review was lukewarm and unimpressed; justifiably, and predictably, the review was, while not negative as such, definitely lukewarm and unimpressed. In the same way, most of the studies that engage past thinking and our past cultural heritage and its productions which sprout forth from our academic publishing factories that are found in every major city throughout the world, ought to receive a lukewarm and unimpressed reception. I said the words ‘publishing factories’ out loud and heard myself laugh. Of course my learned reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement wanted to know about the broader narrative of the material under consideration, wanted to know about the broader historical backcloth and the representative nature of my material. But I could not extrapolate more than my material permitted me; it was not my job. I always knew that I had to show restraint and that I could never, would never allow myself to conclude beyond what my very specific and highly eccentric material enabled me to conclude. I had no doubt that a literary scholar, or a religious historian, or a close family member would have proved more sympathetic to my study, and reviewed it more favourably in the Times Literary Supplement. At this thought I smiled: Yes my dear sister who now sat next to me, academically astute as I know her to be, and who had immediately, and without a moment’s hesitation flown all the way from Denmark to sit by my bedside next to my wife as I was facing heart surgery in China, would have been the ideal enthusiastic reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement. In any case, we may perhaps have to conclude that misunderstanding is the norm rather than the exception. Similarly, and to my surprise (though, on reflection there is really nothing surprising about it) the few scholarly studies that I found to cite my work do so with reference to points that I regard as marginal or tangential to my main insights – things of secondary or minor importance, as it were, in relation to my few useful aphorisms. As regards one’s written legacy, so I thought, we are in error if we expect great effects from tiny ideas, and one can only hope to not be warped, to not have one’s words twisted, beyond all common sense and decency; finally there is little we can do, except to keep on writing, weigh down those shelves, and seek to make a tiny imprint on the world in that all too brief intermission when we have been permitted to inhabit time and space; an intermission squeezed in between two domains of perpetual silence.

Pre-Op

This undisciplined flow of reminiscences and poorly thought through reflections on mortality and human legacy was what rushed through my mind on the evening before my scheduled operation the next morning, as I sat on the toilet in my small bathroom and confronted a secular problem of an entirely different order. A nurse had previously subjected me to a comprehensive hair removal ritual shaving off any hairs that may interfere with the procedure; gone were hairs on the chest and tummy region, which of course was understandable; I was far less sure what possible scenarios they had in mind when all pubic hairs were removed and half an hour was spent shaving my armpits with the utmost scrupulosity. Now this same nurse had given me two plastic injectors filled with lubricating jelly with instructions to empty the contents into my dear old so-and-so, wait patiently for five to ten minutes around which time my bowels ought to vacate themselves quite emphatically. I assume that as I sat there, alone and with my pants around my ankles, and looked at my reflection in the mirror opposite me holding the injector in my right hand, I had in a sense already made up my mind that this was one part of the operation I would have to forgo if I was to maintain a modicum of dignity and ever be able to look myself in the mirror again. I guess that in case I were to wreak some havoc on the operating table, the doctors would also have to acknowledge that as a patient one has many ways of showing that one is still alive.

The following morning, at precisely 8 am I was fitted in my green operation dress, transferred to a gurney on wheels with raised sidebars and supportive pillows on either side of my body that made it almost impossible for me to turn to observe the crowd of nurses, anaesthesiologists, and hospital porters that had gathered round me. The unrelenting chatter in Chinese became muddled and indistinct as I lay on my back and focused on the lights in the ceiling, then I was brought into the elevator, a sister and a wife in either hand, comforting words were spoken, and we got to the fourth floor where the operating theatres were located. During what seemed like a long journey to get to where I was meant to go, I looked at the many signs that hung from the ceiling and pointed to the various hospital departments: Ultrasound Department, Radiology, Nuclear Medicine, Surgical Equipment Room, Intensive Care Unit, and, right before the large automatic doors leading into the operating section, Forensic Pathology. I had to look again in disbelief, and my head gave a little shake before it was in control again. ‘Forensic Pathology’, that was indeed what it said. This was the department they took deceased patients to in order to determine the cause of death. Behind those doors autopsies, post mortems, were conducted. My first thought was that to have forensic pathology located right next to the operating theatres, and to signpost it so clearly, was utterly inappropriate, a bizarre memento mori, although I immediately acknowledged the practical nature of the location. It seemed a taunting reminder to patients already frightened en route to operation, that there is always a statistical possibility of complications during your surgery, in which case this is where your relatives may find you. Equally shocking to me, upon reflection, was that I knew only of a society in which the dead were cleared out of our way as quickly and as comprehensively as possible. Our society undoubtedly seeks to obliterate death, it is a blinkered culture with regard to death one might say; it keeps it off the agenda (or it relegates a surplus of graphic death to mass commercial entertainment such as computer gaming or movies). The actual dead remain the waste matter in the world of the living, which ought to be removed with haste, so we seem to believe, from human society, to be disposed of underground and out of sight. I was only able to think of institutions in which the dead are kept at ground level, or, more commonly, in morgues located in hospital basements, that is before the time when we sink the dead person or that person’s ashes into the ground. To conduct work on the dead on a fourth floor, that is, comparatively high up in the building, seemed to me shocking and practically inconceivable.

Soon I was on the operating table underneath a myriad of softly shining lamps, around me were numerous masked people, everybody looking alike, but each clearly with a specific task to perform. Time seemed to slow down as I lay for what felt like an eternity, listening, hyper-alert, to Chinese conversation and to the sound of countless plastic bags being opened. Perhaps, I thought to myself, the artificial heart valves that were to be implanted were being unpacked from their sterile bags. Amid the buzz of activity and dampened voices I recognised the voices of Dr Wang and Dr Wei, my valve mechanics, and I felt a nurse’s warm hand on my shoulder. Looking back on the experience, jotting down these notes in recollection, it felt like the fundamental qualities of time and space were being reconceived at that moment. Two score and five years ago, when light was first lit in me, I lay, much like now, naked, hairless, and extremely vulnerable, being utterly dependent on others for my survival. In my infant pre-enlightenment, I was as yet unaware of time, and the physical and material world had just begun to open up for me; I was a consciousness that had not yet differentiated itself from the people and things around me. I took in nourishment from my dear mother’s breast but considered that breast as part of myself, being as yet unable to perceive it as anything external to or other than me. Now, as a doctor was about to put his hand on my heart, I felt, for the briefest of moments, a warm sensation of wholeness; all of the masked, anonymous individuals in the room, once infants like I was, had congregated at this specific moment and location, doctors had trained abroad and had come here to join efforts, and right outside sat two anxious ladies holding hands and waiting, all this to ensure the well-being of one gravely endangered patient, an insignificant mammal on a disappearingly small planet in an unfathomably large universe. Lying in the warm glow of the operation lamp, being filled with a marvellous surety, and thinking that all will be well, that all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well was my last recollection before the lights went out.

Emergence

If we permit ourselves, at least momentarily, to relax our stringent logical standards and to take some liberties by means of lexical ambiguity, we might refer to general anaesthesia as a kind of minor death, or to trespass into the domain of the paradoxical, perhaps as a provisional death in life. Perhaps we may regard death as a kind of residing in a permanent state of general anaesthesia. Certainly the two categories of death and anaesthesia have in common certain features, such as paralysis, amnesia, analgesia, that is numbness from pain through the suppression of the central nervous system (Greek anaisthēsia; ‘without sensation’). I think of both categories as processes of quiet extinction. General anaesthesia means an absence of mind and awareness that can, naturally, never be directly experienced by us. In this state we have no mind activity; no thinking, no imagining, no sensing, and no perceiving; we have zero perception of the passage of time and, as far as I know, though I feel less sure of this, no dreams. I have yet to hear of a person just woken up from general anaesthesia who is eager to share a vivid dream they have just experienced. Even to describe the absence of cognitive functions of the brain during anaesthesia as a black void, or a blank nothingness, feels like taking liberties with language, it feels like bestowing on the experience of it some random though minimal conceptual and cognitive content, for who am I to say that my experience of being anaesthetized was an experience of blackness (as opposed to any other colour) or of blankness? No, anaesthesia cannot be a recollection per se, it cannot be an experience for consciousness, it is nothing but a concept of the mind, and anything we say about being anaesthetized, any term we invoke to describe it, reveals much about our capacity for imaginative thinking. The mind abhors a vacuum, it has been said, and when memory is blindfolded it is in our human nature to superimpose qualities, such as blankness and duration, calm or comfort, and we do this solely from the point of view of our awake and conscious state. I imagine that I didn’t feel bored during the four and a half hours that my operation lasted; I have no recollection of feeling impatient for the doctors to finish up soon. I imagine I had no awareness of duration, of four hours and thirty minutes elapsing or of a specific order of events, with the perception of an order of events being essential to our understanding of duration. Until further evidence is presented to me, I take death to mean the irreversible shutting down of our systems, including brain activity and consciousness. Anaesthesia, on the other hand, has the great thing going for it that it is reversible, following a period of mental confusion as the brain reboots itself. General anaesthesia means the use of reversible brain suppressants to produce temporary unconsciousness and it allows for the subsequent reconfiguration of our mind, the absolute re-formation of our mind, memories and self-awareness; in short, the re-formation of our character. And it is this last quality that makes general anaesthesia a hugely attractive option to the person eager to get on with life in a state of normality.

This is not the place to abandon ourselves to further meditation on this subject, which I must say has always fascinated me, but which also takes us into a dizzying terrain of inscrutable epistemological mysteries about death and consciousness. My first recollection, as I was emerging from my sleep was of an eerie temporal and spatial confusion, I raised my head, as far as was possible with the pain in my chest, to look round the room in the intensive care unit but saw only rows of empty beds. On the wall was a clock that showed seven o’clock, evening or morning I did not know. Then I felt the far end of my bed being weighed down, and a hand, warm and bony, sliding into mine, and through a half-haze I perceived a figure whom I recognised as Dr Wang, my valve mechanic, smiling. “Good morning Allan, the operation went very well. How are you feeling now?” I’m not sure if I ever answered the question for I was too busy trying to find out how many cables and wires were attached to my body and what they were. To my chest area were attached electrodes connected via an array of wires to a monitor recording vital signs. A catheter appeared to enter my chest under the bandages and when I reached down to check on my reproductive organ, an act which I was once told all guys do first thing when they emerge from an operation, I noted that a thin plastic tube had been inserted deep into my urethra. I imagine that some junior doctor would have been tasked with inserting the tube as soon as I succumbed to the anaesthesia. Right there and then I made a solemn pact with myself that this was one procedure, an operation within the operation as it were, the details of which I would never again contemplate for one single instant of what remained of my earthly existence.

Hospital Quotidiana

In the weeks that followed I was sucked into the standard quotidian hospital practices that take place in a cardiac surgery ward. These included three hours of intravenous antibiotic treatment in the mornings that kept me chained to my drip bag and to bed, and one hour in the evening, as well as endless row of blood drawings, frequent ultrasound scans, MRI scans and X-rays. I now think of the time as an enforced retreat spent in my room; on the face of it, and to look at it in a positive light, a time of what the ancient Romans called ‘otium’, as opposed to ‘negotium’, the tawdry world of business and of time-consuming and personally sapping labour. I confess that I have always considered true release from work a fundamental good, and I have never really bought into what seems to be a prevailing outlook in our culture, certainly one perpetuated by our ruling managerial classes, that humans are particularly impressive when they are useful, and that the short, licensed vacation reaffirms the value of work and recreates energy for it. Yet, here I was, with an abundance of precious thinking time on hand, an opportunity to abandon myself to the most serious meditation and productivity, but found that I was incapable of thinking a single useful thought, let alone concentrate on my reading and writing. I had a throng of disjointed thoughts, and my soul and mind were capable of sweeping across a million leagues in a single instant, yet my senses were no longer transmitting any useful or coherent ideas to my brain. One needs tremendous discipline to get any work done in a hospital environment, where simplicity and common sense mixed with a good appetite and sound sleep are worth infinitely more than astuteness of mind. I stubbornly refused to abandon myself to the vacuous and stupefying trivialities of Chinese day-time TV shows that were so eagerly but passively gulped up by my caregiver, Madam Lee, who occupied the other bed in my room. Lying in bed, feeling the full force of an inexplicable and irrational melancholy crisis, I saw my online activities drift progressively in the direction of the morbid and misanthropic. I came to embody one of the central paradoxes of our digital age, namely that a great portion of what we do online actually has the effect of making us feel uncomfortable or agitated. It seems we are prone to read about things we loathe, especially so in my case, feeling that melancholy had cast its dark veil upon me. Thus, for instance, I began to study minute details of my ailment, studied pictures of mechanical heart valves and of surgical bone saws, similar to the one that would have been used to cut vertically through the middle of my sternum to allow access to my heart. Online I found easy and oddly gratifying indignation as I indulged myself in the endless toxic spin and propaganda of Chinese state-controlled news outlets, tragically the main fare and chief source of news for such a large part of the planet’s population, and I spent more time than I ever had scrolling through my contacts’ updates on social media sites, in essence a massive onslaught of stupidity and banality, with people broadcasting themselves endlessly, transmitting their small, carefully filtered lives, by uploading an archive of the self, in the form of daily news, images, and updates on meals consumed. It struck me more forcefully than ever before that this absurd theatre of proliferating digitised narcissism was little more than a social media footprint we leave for future generations; that our obsessive self-broadcasting, it being spectacularly inconsequential and insignificant in the here and now, is ultimately us writing our own comprehensive obituary for when we are no longer here, or have been upgraded by biotechnology and AI into something different.

Well, in my case, discomfort and irritation were clearly on the rise and the mind, if it is so disposed, can find causes of sadness and agitation everywhere, as it floods with dark ideas and tragic images. Thoughts do not just leave when we ask them to, we cannot just usher them out. Thoughts can take root and produce irritation. A thousand prejudices besiege us, and in vain I tried to drive them away, but they kept coming back, albeit in smaller and smaller magnitude, so I finally had only very slight worries about my ability to reintegrate into society after the about six weeks the doctors said were necessary for the antibiotic treatment to drive out my dismal bacterial infection. The nurses helped me shake off boredom and lethargy. On their daily inspection round they swarmed into my room early in the mornings, a host of heavenly cherubs perceived by me in a haze of half-sleep, in a group of about eight of them, led by the chief administrative nurse, but as there was usually very little to report or to say they usually just smiled, said ‘good morning’ and then exited my room. In the group was Lele, a junior nurse of twenty-four years of age, of a very distinct beauty with flaming cheeks and an alabaster neck, who smelled ever so faintly of sandalwood soap. She was the only person on the team to speak impeccable English, and she also showed an appreciation for irony rather rare in these parts of the world, and across language barriers. What was interesting about Lele was that she espoused a highly peculiar, and, I dare say, idiosyncratic set of aesthetic principles, using words such as ‘beautiful’ and ‘wonderful’ to describe my long, vertical operation scar, which for a long while after the operation, in fact right up till now when I am making a record of these memories, I lacked the inclination to look at directly. When asked how my scar was healing up, as she came in to clean and disinfect it, she would utter something like ‘It looks beautiful, unbelievable’ or ‘it’s wonderful, perfect, absolutely…’, while she shook her head slowly, but not in negation of what had been said, more as if in disbelief at what she saw.

Cheekily, I greeted the chief administrative nurse in the cardiac surgery ward, whose name I never knew, as Nurse Ratched, confident in the knowledge she would never get the reference to the steely, passive-aggressive tyrant nurse from Ken Kesey’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. She had a rather austere disposition, a sturdy build, rough features, though not unkind eyes, and graying hair. When she entered my room to take my blood, usually about 6.30 in the mornings, she had a peculiar habit of advancing into the middle of my room followed by a group of trainee nurses, and she would stand right there, her arms folded, surveying the room, expressionless and without movement. Then I would stick my arm out, like an obedient child. She was a somewhat rough-mannered phlebotomist, it has to be said, completely disregarding the reputation I had acquired among the nurses as being unusually sensitive to pain and uneasy with needles. She was not rude, just perfunctory, but she always tightened the rubber tourniquet forcefully around my upper arm to look for an accessible vein, and always pulled hairs from my arms while ignoring my moans. At such moments I felt some agitation in the noblest part of myself. It never came to altercation between us. When I did appear brusque, she would invariably take the first step towards reconciliation, giving me a smile that spread to her eyes or briefly caressing my hand, and this would cause me to fill with warmth instantly and to feel some strange intimate bond between us. As a nurse she was superlatively skilled. She was the only nurse to insert a hypodermic needle into my arm so I never felt a thing. As I lay on my back and looked into the ceiling uneasily awaiting the needle prick in my arm she would suddenly tear off the tourniquet, stand up abruptly, put the two filled blood test tubes on her little steel medical trolley and pronounce the only English word I ever heard her use: ‘Finish!”, before she rolled her trolley out of the room.

Pacing up and down the corridor of the Cardiac Surgery Department were patients, all of us having just undergone heart surgery, all supported by a relative or their caregiver, and all wearing the same type of chest compression band to help us stabilize the torso and immobilize the chest wound. Here I walked, supported under my left arm by my caregiver, Madam Lee, who was also pulling the metal rollers with the intravenous drip bags swinging from hooks. In my right hand I carried my pacemaker, a small, heavy black box that monitored my heartbeat and delivered an electrical current via pacing wires put on to the heart. I found this to be a good way to travel as long as I was not in any hurry. When observed from a distance these patients promenading up and down the corridor called to mind the phantom figures in an Edvard Munch painting, melancholy characters, silent, faceless, yet each looking out directly towards us with vacuous, hollow-eyed stares, as if under hypnosis. As I sat and looked at my fellow patients it seemed to me that each walked as an isolated, detached figure, alone but next to someone. Each had their own life and story and each had been visited by their mortality in their very own way, which would have set forth a distinct and unique train of thoughts, comprehensible only to themselves. Yet when our paths intersected in the corridor I always saw their faces light up, as we nodded to each other in recognition and greeted one another with a brief “ni hao”. From my fellow patients, a mass of solitaries, all identically clad, I sensed nothing but optimism, sincerity, and cordiality

. When I lay in my bed and turned on to my right side to look out of the window, my eyes were met by the sight of one of the most remarkable phenomena of our modern era, namely that of China Rising. Enormous cubes of office space were shooting up around the hospital like bamboo after rain. The majority of these were the headquarters of publicly traded companies, mostly in the tech industry, and in fact the Sun Yat Sen Hospital is located inside what has now become the Nanshan High-Tech Industrial Park. Of course, to call it a park involves a complete negation and reversal of any dictionary definition of park as ‘an area of natural, semi-natural or planted space set aside for human enjoyment and recreation or for the protection of wildlife or natural habitats’. Everywhere in this utterly denatured land of concrete, on the ground and on top of buildings, are seen tall tower cranes, these yellow metallic megapods on which no birds choose to sit. I must have spent hours lying in bed observing these towering swinging cranes that cast vast shadows and broke up the rays of the sun falling on the surrounding buildings in a thousand different ways. I was filled with a strong desire to cut them down, as you cut down a tall tree with a sprawling crown that casts a shadow on sunlit days: The cranes irritated me and they obstructed my thinking. They mocked me, as I lay in bed, with their unrelenting industry, with their obscene yellow colour, and unnatural and effortless 360-degree rotation. I wished to cut them down with a crane axe, and neatly stack the parts up against the buildings that they helped erect: all those bland faceless structures, with reflecting facades, that confine people in cardiac surgery wards, or in immense office spaces with countless rows of cubicles in which workers toil away at their screens on their little projects; all of them buildings that every sane person would prefer be outside of, rather than inside. When evening time came I lay in bed looking at the lights that shone on top of the cranes and a few surrounding buildings, trying to predict the intervals with which the lights flashed. I would then sometimes be warmly reminded of the pleasures of contemplating the starry sky, an experience that will never lose its fascination and novelty to me. Some of my clearest childhood memories were acted out under this the greatest show on earth. As a village dweller in my younger days, I would often walk across a field at night and look at stars, or sometimes even row a boat into the middle of a lake, lie down on my back and look for shooting stars, or marvel at the hazy band of white light that is the milky way, what even the ancient Greeks looked at in awe millennia ago and called the, galaxías kýklos, ‘milky circle’; I was a tiny spectator confronting an immense and eternal spectacle, and realising that for the brief while we reside here under the heavens we may understand ourselves to be neighbours and associates of an eternity. Here in Nanshan District, where darkness has been effectively conquered, and where entire precincts are lit up at night like football stadiums, the visibility of stars is of course much reduced. The only true merit I can think of for the cranes is that they provide the towers for mounting the lights that may allow people’s minds to wander off to the galaxies and to at least begin to toy with the ideas of incommensurable remoteness and an infinity of worlds. They may remind dwellers in this metropolis where the lights never go out, of the marvels that remain out there.

One early morning as I lay in bed and was occupied with the contemplation of medicine and the progress it has made since Hippocrates, I noticed out of the corner of my eye an infinitesimally tiny figure on the long climb up the tower of a nearby crane. Once up, this crane operator went to sit in his small cabin, and almost immediately the crane swung its operating arm and parked it in the exact position that it pointed into my room, room fifteen on the eighth floor of the Sun Yat Sen Hospital. It remained in that position for a long while and provoked an irrational fear in me. Performing mental calculations, I worked out that if the crane was a cannon and it fired a cannonball, the missile would end up precisely in my bed. I signalled to Madam Lee to pull the curtains shut, making also a signal with my hand that the light from outside blinded me. She did as I requested and then I picked up a book to read. In my cunning I had managed to make Madam Lee believe that the strong sunshine from outside obstructed my reading. She never for one minute suspected, I am certain, that I had asked for the curtains to be closed because the sight of a crane had become too agitating. Had she known that she got up to do what I asked her to do because a crane was pointing directly at me, and not at all because the sunshine prevented me from reading my book and, she would most certainly have worried about my about my mental state, and very possibly have called my wife to inform her of my recent worrying development.

That very same morning when I managed to defeat the cranes, I had woken up in a state of agreeable turmoil. Four weeks had been spent in the hospital by this time, nearly all of this time in my room, except for my endless pacings up and down the corridor, and even one or two escorted strolls around the outside of the hospital building. Madam Lee had escorted me to the hospital canteen for an early lunch, but finding the food there to be consistently atrocious, and on this day exceptionally unpalatable, we looked at one another and made a signal to get out of here. Feeling a rebel spirit settling upon me, I knew I was in the mood to fling myself into the world and enter its resounding tumult. We walked to the guarded entrance of the hospital perimeter where a sceptical guard asked a few questions of my companion, but finally seemed to be satisfied to release us. Thus for the first time in a long while, I had moved across an invisible frontier, from the land of malady, where one was confronted with an abundance of frailty, into the land of the well. Here were children whose agility seemed to give them wings. We crossed clogged and anarchic roads, and walked along clogged and anarchic pavements, always with the caution of someone who had just entered the world, always turning to make sure we were not being moved down by the fast-moving and silent e-bikes used everywhere in this vast land to deliver packages and cheap, substandard meals. I had broken out of my captivity. Such a grandiose plan! Such boldness in its execution! Having finally turned my back on the bland and sterile hospital environment where no strong colours were to be found and where even the food was not allowed to have any taste, I now found nature to possess a new aura: the sun shone with a new splendour, of that I was positively certain; flowers emitted new scents; colours possessed a new radiance, new intensity. And all this seemed to go unnoticed, unappreciated by the host of indifferent people that weigh down the globe. Occasionally, in this land of the well, we would encounter other fugitive patients wearing the same blue-striped clothes, the same chest compression band, and the same macabre-looking port attached to our hands through which our recovering bodies would sap up life-giving fluids, and we would nod at each other in silent acknowledgement, as if we shared some secret understanding, or were members of the same secret society. From the hurly-burly of chaos in this land of the well, Madam Lee and I entered a street restaurant where I ordered rice with fish-fragrant eggplant, a dish traditionally associated with the cuisine of Sichuan province. The food was a revelation but the strong vinegar and pickled chilli peppers were a shock to the palate and set in motion a fit of coughing so painful I was certain my chest would burst. Also, sweat had begun to trickle from my upper body under the oppressive strain of my chest band, and I had begun to yawn. It was time to leave behind this wilderness of the world, at least for now, and to let my small, safe, air-conditioned room fold around me. In short, it was time for my afternoon nap.

Discharge

When the time finally came for me to check out of the Sun Yat-Sen Hospital, about two weeks after the escapade related above, it was time to say farewell to those who had become familiar and friendly faces over the preceding weeks. Hands were shaken eagerly with Mr Hu, the patient who never wore his chest band, but who instead presented himself to the world with his shirt open and chest bared, showing off an impressive pink-coloured operation scar, like it were some trophy, or a tattoo of which he was infinitely proud. I even saw him promenade outside the hospital grounds along the row of street restaurants where Madam Lee and I would sometimes go. There he walked with his head held high and his chest puffed out, as he turned many a head from the surrounding traffic. I cannot say this turned me off. Patient Hu, like myself, would have paid a princely sum of money to have his procedure done, and it was entirely within his right to show off the surface scar. It also showed a degree of comfort with the wound which I could only admire, knowing, as I did, that it would take long before I would be comfortable showing mine off in public.

The older short and stocky man who occupied the room next to mine also came to shake my hand warmly. He was not himself a patient in the hospital but was accompanying his wife, who immediately after her heart surgery slipped into a coma that was to last nineteen days. I recall how, one morning, as I was sitting in the small communal area at the end of our long corridor, eating oranges expertly peeled and diced for me by Madam Lee, and observing, as I so often did, people coming in and out of the ward and nurses and doctors going about their work, this man man threw himself at the feet of the doctors doing their rounds and begged them, with loud sobbing and tears welling up in his eyes, to do anything in their power to save his wife. In sheer desperation he even offered to pay up any amount of money necessary to bring this about. ‘Begged’ seems such an inadequate word for how he threw himself down at the mercy of the doctors in a fabulous display of sorrow and pathos; ‘Beseech’ or ‘implore’ are the right words to describe the high level of anxiety and urgency with which he made his earnest request from a kind of subordinate position. It was an expression of heartrending helplessness and grief, but a grief that thankfully was not to last long. When I said my adieus to the gentleman in the corridor his wife had been returned from the Intensive Care and was sitting on a chair next to him outside the door to her room. This petite and frail lady, at whom death had just fired all its darts without entirely hitting, sat and looked into space with an empty distanced gaze. I greeted her also, but she remained silent and appeared to look straight through me with a look that suggested to me she had seen things that no human should ever have to see.

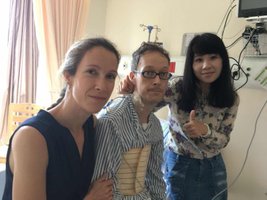

Now, as I look back at my six weeks spent in the Sun Yat-Sen Hospital, already more than a month in the past, I think of it as being enveloped in a dense gloomy fog, in a sort of milky melancholy in which I felt, never miserable as such, but rather numbed, disquieted, anaesthetized, and incapable of feeling passion of any kind. The days were punctuated by routine practices of blood testing, CT scans, x-rays, infusions. But most days were indistinguishable; only the days in which I received visits from friends where we chatted, played backgammon, or shared a pizza occupy any space in my memory. Other than that it was all a desert of uneventfulness. Time did not seem to move forward in a straight line, but rather to reappear in the same form. In retrospect the string of typical days shrinks to nothing precisely because of this uneventfulness. In the perspective of the past such interminable hours and days appear to have no extension, no volume, their weight in memory seems lighter than air.

Getting out of hospital was not an altogether simple affair and involved complicated feelings, often of a negative sort, and frequent mood swings. When frigid reason took control the reason why this was the case was easy to explain: In our normal mode of living we have a tendency to assess the quality of our lives through the positive and exciting experiences we add and by the material things we acquire. That is to say that, when we are fully in control, our lives are perceived as a form of simple addition. By contrast, in hospital, and during a long period of sickness we perceive mostly the desirable things that were once experienced but that are now absent to us; at such times the subject is confronted with mountains of subtraction. Thus, as I was lying in my hospital bed I focused on my absence of mobility, an absence of appetite. My libido felt detached, and I experienced a general lack of enthusiasm about any of the things that usually matter to me. I was a version of myself, only minus sleep, minus a job and minus money. I found myself unable to do any writing or reading – I could barely read headlines. Moreover, I discovered two basic rules that apply to this state in which life is perceived as a form of subtraction. The first one is that fear does not count as an addition, in fact, this feeling works in reverse and is actually perceived in the mind as a form of subtraction, whether this was the fear experienced prior to the operation or fear felt in the weeks after; fear of the daily needle prick, or a fear of having the metal wires from my pacemaker pulled out from my chest. The second rule is that when life is experienced as a form of subtraction, the argument of the ‘lesser evil’, the argument that there is always someone who is worse off then you, does not count for much. So, when people made quantitative comparisons (‘what about the eighteen-year-old guy in the next room, he has been staying here for two whole months’, ‘think of the lady who went into a long coma after her operation’, etc.) I found these to offer only the tritest of consolations and they did almost nothing to make me feel better. Experiencing a prolonged period of subtraction can mean dejection; it may dampen the spirit and cast a veil of gloom on us. Any abrupt reversal from a period of subtraction into a normality governed by simple addition, which means to most of us a gratifying worldly compliance with fashionable customs, takes considerable time to register as a positive development at the level of human sensitivity; it can never occur suddenly, as a change overnight.

Rambling through Kennedy Town

For convenience sake I had arranged to have my monthly check-ups done in the Queen Mary Hospital in the Pok Fu Lam area of western Hong Kong Island, in order to avoid the long journeys up to the hospital in Nanshan in Shenzhen. On the Tuesday morning over a month after my operation, when the doctor said the words “it looks good, we’re on target”, he was referring to the index for the coagulant and clotting tendencies of blood, expressed in the number known as the INR (International Normalized Ratio), which for a normal person not taking anticoagulant medicine should be around 0.8-1.0, but for a patient with mechanical heart valves is ideally between 2.0 and 2.5, which means that blood runs thin and bleedings can be very difficult to stop. The INR number is notoriously volatile and easily influenced by diet and various other factors, and on this day my INR was determined at 1.99, in other words at the lower end of the spectrum, which meant that I had to make a minute change in the dosage of my warfarin pills, specifically to increase it from 2¼ pills per day to 2½. It was an adjustment I was rather relieved to make, because it had proved very arduous to have to break the tiny blue pill into a quarter. I said good bye to the doctor, walked out of the small consultation room, and got on the small green minibus line 54M which sped from the Queen Mary Hospital down the Pok Fu Lam Road and Smithfield into Kennedy Town in the north-western part of Hong Kong Island, along a route which offered splendid views of islands and sea and the enormous Christian Pok Fu Lam Road Cemetery, whose seemingly endless rows of terraces and interconnecting staircases have rolled from the upper contours of the hill down to the lower slopes by Victoria Road since the cemetery’s establishment in 1882. As I sat in the bus and looked out over the sea, I rehearsed the conversation I just had with the doctor over and over. This was a habit I had begun while in hospital; to interpret every word and intonation, to accord significance to every gesture, every little facial expression. I reacted to friendly or worried expressions like a seismograph. I got out of the minibus outside the Kennedy Town MTR Station. It was the hour for business and other vexations, and as I began to float through the streets I abandoned myself to a torrent of people that swept me away. I had to fill the present afternoon somehow, and it was now only about one in the afternoon, so I went into a Pacific Coffee store on the corner of Belcher’s Street and Davis Street, and checked the cinema listings in a local paper to see what was playing. Mission Impossible – Fallout, the sixth instalment in the series had just opened, as had the action film Skyscraper, set in an imaginary skyscraper in Hong Kong featuring the actor Dwayne Johnson, a former professional wrestler known by his ring name The Rock, and by media proclaimed as the most ‘bankable’ actor of our era. But my mind was not ready for spectacle, fast cuts, special effects, and all life’s complexities turned into recognisable plot forms. I knew that in my current state I would fall asleep in the cinema. I knew I would not be capable of watching any of the shows through to their ends. I was happy to let the cinema go and instead I left the coffee shop and began to stroll through the streets of Kennedy Town, one of my favourite places to walk in Hong Kong. The weather was balmy, benign and beautiful as I made my way down Belcher’s Street, walking in a kind of half-dazed state, never entirely connecting with the surroundings. Everything stood out for me as foreign, as somehow inconceivable, and people, to the extent that I noticed them, seemed unnaturally small. I felt almost weightless, bodiless, and walked as if I had mastered the art of levitation. It really is possible to feel like a ghost among fellow men, like some doppelganger or revenant that walks around without at any time entirely connecting with the physical surroundings, and feeling a complete aloofness from ordinary sublunary anxieties. Surely, I thought, this state of mind in which the outside world has become unreal to one, in which the millions of stimuli that bombard the human mind are somehow not perceived as real, ought to be recognised as the innermost mystery of secular metaphysics. Lavishly funded research projects ought to be set up in which cognitive scientists, neuroscientists, philosophers, and psychologists join ranks with poets to get to the bottom of this very human mystery. If any thoughts impressed themselves on my mind in its present state it was in the form of memories of consultations and conversations with doctors and nurses that I had experienced over the past weeks. ”Remember, walking is healing”, Dr Wang once said to me as we were discussing life after the operation, a statement that seemed to me at that moment to contain deep wisdom, deeper perhaps than was intended. Now, as I was rambling through the streets of Kennedy Town, I thought about how a constant in my life has been my liking of solitary walks and being continually curious about what I see.

As a child, I was lucky to have parents that did not drive my sister and I around everywhere, parents who let us notice things we could never see from the interior of a car. I enjoyed walking even before I knew I had a name; walking was as natural as breathing, and was often filled with rich exploration. To this day I know of few things better than exploring a new city on foot; it is fascinating the things you see when you are on foot and bother to look around. “That far!” people often exclaim when I tell them about walks I have undertaken, a response which often surprises me because my walks rarely feel very long, and it seems quite redundant to have to point out that there is no better and cheaper way than walking to sort our thoughts and keep fit. Looking back, all the way back to the time from which memories now flood back as feelings and not as words or images, I realise that it was the act of walking that connected me with my community at a pace predictably, inescapably human. Many of my earliest childhood memories are of specific walks; frequent walks with my parents through the forests that surrounded our town, adventurous and dramatic hikes as a boy scout, often in the middle of the night, and walks from my town across the fields or through forests that seemed endless to a neighbouring town where some of my classmates lived. These long walks with childhood friends were utterly daunting at the time, and they were walks whose logistical details were planned in intricate detail long in advance; the precise route was planned using local maps, food and drinks were packed, permissions were obtained from parents, emergency phone numbers were written down (not unproblematically as this was a time before mobile telephones). Of course, today when I revisit these same places, the distances over which these mini-adventures were acted out seem laughably short, the proverbial stone’s throw away. Is it not possible, I now thought to myself, that everything happened on those walks? Is it not possible that the walks determined our future, and that nothing in later life exists apart from those early walks with our childhood friends? Those people that we looked up to, those whom we mocked, and those we had a crush on, even the very rhythm in which we spoke to each other; all was determined on our early walks. In fact all the operations of our adult intelligence were present in miniature as we walked together, as were all the sensations, perceptions, feelings, and intimations of feelings that we would later experience over and over again. When we walked through the landscape of our childhood, along the edge of a forest whose colour was ever changing, we became who we were to be, and incidents happened that would influence us for the rest of our lives.

And then of course there was the most important walk of all, the one I performed every day over years, from my primary school up the steep and prosaically named School Road to our local library, a walk often undertaken with groups of classmates through streets that now hold many memories. This was a walk to the library building that was our chief forum of entertainment, a walk to the building that belonged to all of us, the place where we devoured cartoons, listened to audiobooks, and collapsed in beanbag chairs with a favourite book in hand. It was in this place that I read books and forgot everything around me for hours on end, and was contented and really cheerful. Here I first lost myself in literature and felt entranced as a child, here I learnt how the printed word when read could summon up physical presence and engrave itself on our memory. And here I had my first memories of having leapt over the wall of self, to be in the mind someone else, to be elsewhere. In this library, in which I happily spent that precious interval between the end of school time and dinnertime with my family, were the windows through which I must have spent hours gazing in a sort of solitary reverie at views I still vividly recall, while my mind indulged in flights of fancy, thinking about what had just been read, savouring moods and impressions, and invariably seeking to postpone the inevitable calamity of coming to the end of a book that had engrossed me; of coming to that final point where I would draw a deep sigh as my relationship with a book’s characters came to an end, characters on whom I had often bestowed more attention and affection than I had on people in real life. A book would be closed and once again occupy a narrow space between other worlds in hard covers – parallel universes neatly arranged on our shelves. But the books would remain our dear friends even after they turn their backs on us. The intensity of these early reading experiences seemed irrevocably lost, or at least transformed, from my present perspective.

”Remember, walking is healing”, my valve mechanic had said to me; an astute comment to be sure. And I would add to that that reading and writing can constitute forms of healing as well. Writing is an act that allows you to understand yourself better; I for one know that there are experiences I only fully understand, or can come to accept, or am able to talk about if I have written them down first. It now struck me, as I was floating through the streets of Kennedy Town, that many of my favourite writers are also walkers, writers whose thoughts developed organically and often in direct response to what is observed during long walks. With the works of thoughtful wanderers the reader’s mind is in an ongoing dialogue with thoughts on the move. I have in mind here not only the old relic of romanticism, the philosopher’s walk (Philosophenweg), the quiet scenic walks that we find near old universities such as Heidelberg or Königsberg, for instance, where poets and philosophers like Hegel, Clemens Brentano, Søren Kierkegaard, Immanuel Kant, and Friedrich Nietzsche used to reflect and discourse on their daily perambulations. Was it not Nietzsche, by the way, who said “Never trust a thought that occurs to you indoors”?

A book that became especially important to me in my enforced retreat of six weeks in the Sun Yat-Sen Hospital was the Journey around My Room published in 1794 by Xavier de Maistre, a French military man and aristocrat. De Maistre was confined for 42 days in his apartment in Turin (he was convicted to house arrest, as I recall, on account of some implication in a duel), and in the small apartment this most endearing of individuals – intense, romantic, thoughtful and bibliophile, walks around at all angles, his attention fixed on objects, visible surfaces, one moment making references to the life led outside the room, the next moment abandoning himself to long (and sometimes rather wearing) digressions on his dog, his girl friend, or his servant Joanetti. Always refusing to keep to a set route, always seeing the familiar with fresh eyes. "When I travel through my room," he writes, "I rarely follow a straight line: I go from the table towards a picture hanging in a corner; from there, I set out obliquely towards the door; but even though, when I begin, it really is my intention to go there, if I happen to meet my armchair en route, I don’t think twice about it, and settle down in it without further ado." De Maistre pioneered a new type of travel – room travel – which he recommended to those who are poor or infirm and to anyone who fears storms, high cliffs, and robbers. His is clearly a pastiche of the grand travel narrative, written in the style of a mock-epic, in which the shortest of distances inside a bedroom can seem like a perilous and uncrossable terrain. But his travelogue is also a great consolation to any person who is alone in a room. Experiencing isolation from society and a paucity of external stimuli, de Maistre uses creativity and imagination to transcend confinement. It is through recollection, imagination, storytelling, daydreaming that he is able to shake himself from his lethargy and offer imaginative musings more gripping than reality itself, and at least as exciting as exotic tales of the South Seas or heroic accounts of voyages to the Himalaya. For some, enclosure can be enabling, if, that is, they possess the right travelling mindset, an ideal ambulatory disposition we could say, with a mind perpetually inquisitive, and a predilection for following one’s ideas and train of associations wherever they lead, without sticking to a set route or the straight line.