The old fountain in the Hong Kong Protestant Cemetery

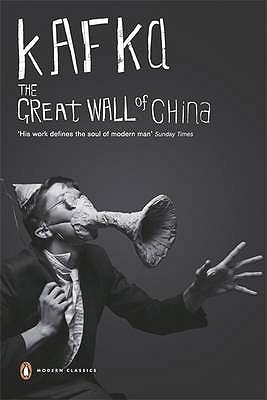

Kafka, "The Great Wall of China" and other short stories, Penguin Modern Classics.

Protesters in Mong Kok,2014

Mr Abelard Looks at Things in Hong Kong

Mr Abelard Walks in Hong Kong Cemetery

Today, the best way to arrive to the old Hong Kong Cemetery in Happy Valley is by the tram that for over a century has been running between the East and the West along the Northern coast of Hong Kong Island. To arrive in Happy Valley means to arrive in Hong Kong’s necropolis, for here are found six cemeteries; the Jewish Cemetery, the Hindu Cemetery, the Parsee Cemetery, the Protestant Cemetery, St Michael’s Catholic Cemetery, and the Muslim Cemetery.

On this occasion, a warm afternoon in August, we enter the cemetery garden of the Hong Kong Cemetery (also sometimes called the Protestant Cemetery or the Colonial Cemetery), and in this place our eyes immediately find rest in a horizontal garden panorama so different from the usual vertiginous perspective of a city in which vast edifices and towers of glass and metal constantly direct the gaze upwards. Here we look out across green lawns with a seemingly never-ending inventory of all the monuments we erect to commemorate our dead: tombstones, marble crosses, stelae, obelisks, sarcophagi, bulbous urns, statues, and stone angles. In this spot the beauty of nature vaults over the dead, trees bend under the dense tropical pressure, and flowers sprout up between stone slabs, or peep out through granite cracks. Here nature insinuates itself at any point. In the Cemetery’s higher levels the graves are in advanced state of disrepair, of wilful neglect one might say. Up here the foliage is unkempt and the roots of trees have toppled granite memorials and bent iron railings. Roots grow out of stone and they pop up between stone work joints. Bundles of thick arboreal roots writhe and well out of granite crypts like grotesque, morbid art installations. How very different this is from the picturesque, gentle decay of the Cemetery’s lower levels, in which the old graves, dating back to the first years of the British colonial rule, have been laid out in in a simple, geometric grid. This section is an archive, a cross-section of colonial society with its own gradations of social hierarchy. Buried here are missionaries, colonial administrators, merchants, doctors, soldiers, policemen, and sailors.

And in the middle of it all stands Mr Abelard, and he feels overcome by it all. This short, elderly man stands for a long time in silence and looks around him. But Mr Abelard is not lost in contemplation, in fact he is not lost at all, because he is quite aware of where he is and what he is doing. He has nothing against contemplation, in principle, but on this occasion, as on most occasions, he is not in the right mood for contemplation and the exterior circumstances are not right for contemplation. “Everything breathes life in this dwelling place of the dead”, he thinks to himself as he stands amid swarming dragonflies and surveys the rows of graves before him. Mr Abelard has arrived to the Cemetery on this late afternoon, at the time when the day is in decline and everything casts long shadows, and now he stands before the imposing tomb of one of the first western missionaries who came to China in the early 1830s. For a long time he stands and looks at the tomb hewn in grey granite, a sarcophagus in an ornate classical Roman style, which is really, he thinks to himself, an amalgam of sepulcher, mausoleum, and cenotaph. The elaborate tomb has cracked in several places and from one tiny, narrow crack, directly above the marble plaque with the missionary’s name on it, a small green plant had emerged and folded out its leaves. Somehow a seed must have found its way into the darkness of the sarcophagus, where it had sprouted and commingled with the bones of the pioneer missionary, and then sent forth one of its branches on a mission to find sunlight and moisture. Mr Abelard stood still for a long time and contemplated the emergence of this tiny green plant from the cracked sarcophagus. He was instantly moved, and that most strongly, by the sight, which he immediately interpreted as a message about his own search for truth in the midst of darkness.

At this stage we have to say that Mr Abelard, a gentleman now in his sixties, is very rarely in a hurry and has always delighted in looking at things until they open themselves up and reveal their full meaning to him. For the past many years – for decades in fact – this small, eccentric man has learned to stop up, sometimes for a long time, to fix his gaze on specific things – on singular, precise objects – to consider all the layers of meaning they possess. If asked about this habit, he would tell us that this means little more than bestowing on things the attention they deserve, but in reality it means to notice patterns not usually perceived by those of us who pass through places hurriedly or are eager to get elsewhere. It is indeed a blessing to have the world reveal itself with an extraordinary and infinite richness of meaning, and to be able to decode messages, allegories, or symbolic representations in ordinary, every day objects. Mr Abelard knows better than most that, faced with allegory and symbol, we have to be active interpreters; we have to seek out meaning, find it, identify it, and interpret it; we cannot be passive consumers of allegories. Allegory may lie hidden right in front of us – we see signs but we may not immediately see their meaning or even begin to wonder about the meaning behind signs. Often it is difficult to pay close enough attention, when so much around us is competing for our attention. Mr Abelard thinks of such moments of insight as instances in which the mundane and the everyday present themselves in a full blaze of light, and they often occur when he is least expecting it. Such is certainly the case on this afternoon when he leans forward to regard the green plant that peeps out from a crack in the granite tomb, and he comes to see in this sight a profound vision of resilience, strength, and light.

From the granite tomb of the nineteenth-century missionary, Mr Abelard proceeds into the middle of the cemetery garden, while dragonflies and damselflies swarm around him and perform their aerial courtship ballet, their translucent, greenish wings glistening in the sunshine. The stagnant afternoon heat brings a trickle of sweat running down his forehead which he gently wipes off with his white handkerchief. Then he finds himself standing in front of the old cemetery fountain, a circular cement pool with gaping cracks filled with dry, cracked sand. It is decades since the fountain contained water, and it stands now as a sadly dilapidated allegory of the Garden of Eden. The fountain is a simple cement fountain, but it contains a grand narrative about our origins and our destiny – made by the earthly hand of man, it is subject to the same powers of decay as man. Along the rim of the central pool Mr Abelard notices the four semi-circular bays that symbolize the four rivers that according to Genesis 2, 10-14 flow out of Eden to the four corners of the world. “The Tigris and the Euphrates…” Mr Abelard reminds himself, but, standing here, his head swimming in the humidity and sunshine, he cannot recollect the names of the other two rivers mentioned in Genesis, which he has read more times than he would care to know. “A senior moment, Mr Abelard!”, he thinks to himself and smiles, and then he promises himself to look it up as soon as he returns back home. The names of two rivers he may have forgotten, but of course the central story of the ancient history of the cosmos he remembers very well: Inside the Garden in Eden God made all trees grow out of the ground – all the trees that were pleasing to the eye and good for food. In the middle of the garden were the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. A river watered the garden which from that point separated into four headwaters. The Lord God took the man, made in God’s image, and put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and take care of it. And the Lord God let man have dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth. And then God commanded the man, “You are free to eat from any tree in the garden; but you must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat from it you will certainly die.”

Mr Abelard would not call himself a religious person and his first inclination is not to look on allegory with the eye of faith. For most of his life he has treated religion with a practical indifference, and he tends to think that there are no such thing as spiritual phenomena but only a spiritual interpretation of phenomena. What little theology he has studied he has studied for himself and purely out of his own curiosity. As he stands and looks at the fountain in the middle of the cemetery garden, the following thoughts occur to him: Put a scientist and a religious person together and they may find very little to agree on; but they will likely agree that at the very beginning of things the cosmos moved from a state of nothingness to a state of the existence of matter. From this basic premise, the scientist (always reluctant to embrace the speculative) will have little to say about this mysterious transition; his narrative will be one of physics and chemistry and biology, and a mysterious Big Bang in which matter and energy coalesced into complex structures, atoms, which then combined into molecules, that again combined to form large and intricate structures called organisms. But the religious person, on the other hand, will give a far more vivid and thrilling account of the history and nature of creation, and he will have behind him a richness of religious and devotional art that gives him many interpretations and allows him to picture vividly what took place. First darkness was upon the face of the earth and then out of the void God created a garden in Eden for Adam and Eve who, like the animals around them, were naked, innocent and not knowing what is good and evil. Man disobeyed God by eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and the act led to suffering, pain, and death. Such is the gist of the creation and fall of man in the garden of Eden, the place which we are to understand as both the place where sin came into the world, and as synonymous with heaven and paradise – a state of unspeakable joy. But Mr Abelard understands that the garden in Eden is not to be confused with a literal garden; he knows the narrative is riddled with problems if one views it literally, from the perspective of history or geography. No, Mr Abelard has always seen the story of Eden as an allegory of how choice and experience develops our moral character. The serpent offered up, like the tree itself, the possibilities of choice, freedom, guilt, and remorse – it delivered man into self-consciousness. Naturally, the fall was inevitable and it was about the natural progression of consciousness into a state of doubt, fear, guilt, shame, blame, loneliness, and frailty – without these, Mr Abelard knows, we would have none of our most exquisite cultural productions.

Mr Abelard understands better than most that allegory is an archaic term and that its origin is theological. Allegory can teach a moral lesson, certainly, but it is also a way of looking at the world that surrounds us. Mr Abelard looks primarily at allegory – at things that signify other than themselves – with they eye of the intellect, and not with the eye of faith. It means for him a process of selecting things to be looked at in this way – things that demand to be scrutinized, unpacked. In this process of selection and exclusion, much is passed over that does not seem to carry much meaning, or does not readily open itself up to him. The old, cracked fountain in the cemetery garden gives Mr Abelard an occasion to think once again about the essential creation narrative and about how it gives us guidance for how to behave and about our destiny.

But now he finds the temperature in the garden quite intolerable. This short, stocky, balding man, who makes no concession to climate walks in his grey flannel trousers, shirt and a tweed waistcoat after a fashion no longer seen and a matching jacket now loosely slung over his shoulder. He turns around and starts to walk towards the cemetery gates. Walking towards the exit, he passes the cemetery’s funeral chapel that dates to the first year of the cemetery’s foundation in 1846. The small chapel is cross-shaped and thus symbolic of the cross that Christ died on. “Allegory finds its natural home in a city’s cemetery”, Mr Abelard thinks to himself.

Mr Abelard Scales the Peak

On a punishingly hot and humid afternoon in late August we take a walk up towards the Peak of Hong Kong Island to get a good view of the city below from a point of elevation. We have climbed up the steep and winding path of the Wan Chai Gap Road, which involves proceeding through the upper edges of urban sprawling, until the city slowly releases its grip and gives way to a thick, impenetrable green of trees and shrubs, ferns and bamboos that spreads across the hillsides. Up here acrid air of exhaust fumes trapped within the maze of city high-rise is replaced by dense, tropical, damp air. We arrive to the Peak Road which winds its way undaunted around some of the most precipitous hillside in the area. And we walk past gated residential communities that offer the privacy and discretion that everyone desires for their own reason; the only people here who appear to do any walking are the domestic helpers, predominantly of Philippine of Indonesian extraction, who dutifully walk the dogs of the eye-pleasing and thick-furred kind which residents seem so intent on acquiring and yet so averted to walking themselves.

But look! Here we have the good fortune of encountering once again Mr Abelard who, like us, has ventured up here in search of interesting things to look at. We follow him as he makes a right turn up the winding and tranquil Barker Road, partly to avoid the sight of thick-furred canines panting in the sweltering and clammy heat, but also to escape the surprisingly heavy traffic of private cars and double-decker busses that take visitors to and from the Peak. Barker Road carves its way around the hillside and will eventually land Mr Abelard on the Peak proper and the upper terminus of the Peak Tram, undoubtedly the city’s foremost tourist attraction. The road he walks is almost entirely walled in by immense fern fronds, thick bamboos, and trees that gather in to meet overhead, creating the striking effect of walking through a narrow cavernous passage. About half-way up Barker Road, Mr Abelard makes out a large banyan tree that stands on a narrow strip of lawn in front of a large building. Extending its branches over well-nigh a quarter of an acre, this majestic growth is a world unto itself: its expansive aerial roots bow down as low as to the lawn and secure a firm hold into the ground. Along the ground and crawling towards Mr Abelard are innumerable meandering roots that resemble plumbing drains or thick cables; they seem immensely powerful and unyielding, capable, he can easily imagine, of uplifting houses. Immediately Mr Abelard is reminded of a formulation by Charles Ford, Hong Kong’s old Superintendent of Forestation and Tree Planting, from one of his annual reports written sometime in the 1870s, around the time when this banyan must have commenced its growth: “we understand the considerable damage that accrues to sewers, pavements, and foundations of house-walls by the banyan’s long straggling surface roots, which travel to great distances in search of moisture, and insinuate themselves between the joints of stones which they eventually upheave.” Mr Abelard has always enjoyed reading the old forestation reports written by Charles Ford because of their miniscule detail and striking eloquence, and for some reason this particular statement about the immense might of the banyan tree had stuck in his mind. In the past, Mr Abelard has often stopped to look at banyans in Hong Kong, but he recognizes this tree on Barker Road as a particular elaborate and muscular specimen, an entire ecosystem, it seems to him, that harbors numerous other growths like fern and ivy, all growing on its immense tangle of horizontal roots and upward thrusting branches. In an instant Mr Abelard’s trained eye tells him that this tree is worth prolonged scrutiny. On this exact spot, he thinks, for almost a century and a half, nature’s plenty has been patiently and willingly multiplying and joining and growing.

We know that Mr Abelard is a person who prefers to keep his sensations under control insofar as possible, and this involves keeping his attention disciplined and closely focused. He has trained himself to limit his field of observation and to put up boundaries of what he looks at, so as to consider the meaning that lies beneath the surface. This has become for him the only way to stay focused and sane in the midst of a hectic and congested world. And now that he stands before the mighty banyan on Barker Road, he feels that the growth asks of him careful and prolonged attention. By now, as Mr Abelard stands before the tree, scattered mists sweep by this part of Barker Road, and the growth appears to him one moment as a specter in a dim, unnatural light; the next moment it stands as an entirely clear structure to be studied in its minutest details. It now strikes him that no other tree has been more deeply enveloped in folklore, fable, and myth. It was under the banyan tree, sitting in its shade for forty-nine days, that the Buddha attained enlightenment; in Hinduism, the thick, elliptical green banyan leaves represent the Vedic hymns, while the god Krishna is said to find his transcendent resting place in a single leaf of this tree. Through the ages the majestic banyan has embodied a lesson of the infinitude and vastness of things. And right now Mr Abelard considers that the allegorical Tree of Life that God planted in the middle of the garden (a material tree in Genesis but really standing for the blessing of eternal life promised Adam and Eve if they pass the test of obedience) might be akin in nature to this splendid growth. At this very moment, the thought occurs to Mr Abelard that the tree might be able to provide answers to our most pressing problems if only we know how to read it; that, from its seemingly unending expansion of roots and trunks and branches, we might somehow be able to divine guidance and reassurance for a mankind who has lost its way in the world.

Does allegory stand at the center of our life, or is it content to occupy just a tiny corner of it? Mr Abelard’s inclination is towards allegorizing material objects and constantly seeing in things deeper symbolic representations. But he also knows that allegory, as a mode of making sense of things before him, is open-ended, inconsistent, and always demonstrating a lack of light. Often, when he feels he has managed to see all, to exhaust all possibility of meaning, something new will crop up that makes impossible any definitive reading and understanding. But Mr Abelard will never stop looking, probing, ruminating, for he may one day cultivate his skills of seeing into a form of cosmic wisdom.

Mr Abelard would be perfectly content to remain in this place beside the splendid banyan tree on Barker Road, but now he wishes to enjoy an ice cream in the Peak Tower shopping mall near by, before taking the Tram funicular back down into town. He proceeds a little further up Barker Road but then stops for a moment to take a final look at the tree and its surroundings, as if to say good bye for now. He feels himself immersed in a stillness such as is scarcely to be found anywhere today in the orbit of our civilized world. Not a breath of air seems to circulate or a leaf to move. A ray of sun illuminates the banyan tree on the lawn a short distance away from the building which he only now really notices. The building, Mr Abelard is aware, is the old maternity ward of the Victoria Hospital, on whose construction work began in 1897 in commemoration of the Queen’s diamond jubilee, but which has now been converted into quarters for senior officers of the civil service. The comparatively miniature and graceful neoclassical proportions of the building stand out in the bright sunshine; all is framed by greenery and overarched by a radiant blue sky. Then Mr Abelard notices a single person, a female uniformed guard, no longer young, standing on the open portico amid decorative arched columns in front of the building’s main entrance. The solitary sentinel waves good bye to Mr Abelard, who is now thinking that she might have been observing him for the entire time that he stood lost in his own thoughts before the mighty banyan.

Mr Abelard Reads Kafka in Mong Kok

Zoom 1

Hong Kong in early November 2014 is a city engulfed in the socio-political struggle of the so-called Umbrella Revolution. At this time, a protest movement with a limited set of political demands has morphed into a defining generational moment whose impact is felt throughout the city, and will undoubtedly be felt far into the future. For almost two months now a gathering of the city’s youth has peacefully occupied the main thoroughfares of the city to campaign for democracy and fair elections, and for the briefest of moments (one suspects) they have received the attention and sympathy of the entire world.

Zoom 2

Mung Kok, a neighborhood in Kowloon, has for several weeks now has been a protest hub, and has seen some of the fiercest clashes between the pro-democracy protesters and the anti-occupy groups that oppose them. Encampments have been put up in Mong Kok on streets with mixed residential buildings and small businesses. Gathered here are protest voyeurs from around the world and a more combative and politically radical crowd than we find at other protest sites in Hong Kong.

Zoom 3

A protest encampment on a main intersection in Mong Kok is bookended by barricades and inside it we find an assemblage of tents, posters, and protesters camped out on city streets. Weeks of protests have forged new social bonds and the sort of generational unity that emerges only when you mix big ideals with high drama. In this location, a temporary, alternate universe has been carved out, with a new social order, with new ways of providing for and protecting one another, and showing the boundless creativity of youth united. In the middle of the encampment a study corner has been put up in which students sit along rows of trestle desks or on yoga mats with their books open. By the entrance to the study corner is a sign: “Please remove your shoes. Help keep the area clean.”

Zoom 4

A small library has been formed in on one corner of the study area, and here are course books, books about politics and political rights, travel guides, handbooks for computer programming, and a full shelf with novels. The library serves a clear utilitarian function, but it is also an effort to open people's eyes to new vistas, in a district where, one assumes, very few books get read. The library in Mong Kok is as utopian a space as any we find in Hong Kong.

OH, but just look! What a most unexpected sighting! It would appear that Mr Abelard has come to Mong Kok this morning. We find him standing by the book shelves in the open-air library, browsing through the shelf of fiction, seemingly unaffected by the tumult here on the front line of ideological struggle. And the gentleman certainly does stand out in the crowd: amid youths dressed for what feels like a 24-hour slumber party, this elderly man with graying hair appears overdressed in his usual jacket and waistcoat. We notice that little pearls of perspiration glisten on his forehead. His attention concentrates on a single volume on the fiction shelf which he takes out to look at. He looks completely nonplussed as he examines the book with a mixture of delight and bewilderment; Franz Kafka. The Great Wall of China and Other Short Works. At this stage we have to acknowledge that Mr Abelard’s familiarity with the works of Franz Kafka is advanced and thorough, and that for many years Kafka’s short story “The Great Wall of China” has been among his absolute favorites. He has read the short story, which he understands as a modern allegory, innumerable times and considers it one of the author’s most profound stories. To find a book with Kafka’s stories here in Mong Kok is indeed unexpected, but Mr Abelard thinks to himself that we should take too mean a view of destiny, were we to think such an encounter the outcome of a random universe. Now he intends to sit down and read the short story once again here in the study corner in Mong Kok, which seems to him an entirely appropriate place to do so. He turns to a young couple sitting in the open-air library.

“Excuse me, would you mind if I sit here?”

he asks them, and the girl looks up and answers

“Yeah, sure”

as she looks to her boyfriend with a quizzical expression, and they smile to each other. Mr Abelard is a solitary individual not usually comfortable in the company of others; he finds that he cannot make sense of people the same way he is often able to make sense of things that present themselves silently before him. Curiosity has driven him to Mong Kok this morning; Generally Mr Abelard’s responsiveness to places is instantaneous and profound, but he is not a political being and has next to no understanding of, or interest in, the political situation in Hong Kong. However, from what little he has read and heard, he understands that the young protesters are fighting for values that are his own. He sits himself down and begins to read “The Great Wall of China”.

Kafka’s historical narrative relates the musings of a nameless narrator from southern China who took part in the building of the Great Wall. He notes that the wall’s status as a coherent cultural symbol is in opposition to the disjointed conditions of its original construction, for the Wall was built in a piecemeal manner as a variety of individual walls that were constructed (and repeatedly reconstructed) over a period of more than two millennia. The precise significance of the wall eludes the narrator, who, living in South china, is far removed from the wall geographically, and is in no danger from the northern raiders beyond the wall. The same goes for the high command in Pekin because, for the narrator, the emperor is too far removed from his own experience to possess any sense of reality to him; the real, living emperor of China is insignificant next to the idea of the emperor, because the vast majority of people in China can never know the emperor as a flesh-and-blood person – they can only access the idea of him. Some of the tactics of the great power game the narrator has fathomed: the emperor has to be impossibly removed from the vast majority of his subjects, because distance is an enabling condition for the emperor’s own power and authority. It is in these gaps between the emperor and his subjects, and between subjects and Wall, in other words, that we find the stuff of legend, including the symbolic authority upon which the emperor’s political power is itself grounded. The high command is“absorbed in gigantic anxieties” and knows that command is only possible if humanity is a fragmented, divided species, and building a wall is all about keeping people divided.

As Mr Abelard sits among young pro-democracy protesters in the encampment in Mong Kok he feels, much more than he had felt before, that he is reading a story with decidedly political overtones. In 1917 Franz Kafka sat down to write a short story; he left a mark for an unknown future – and what he left us acquires a meaning he could never have foreseen. And now Mr Abelard thinks to himself that, historically we have always been subservient to the emperors; making money for them, building their monuments, their bridges and towers, their walls, obeying their commands.

In Kafka’s short story, doubt is expressed about the meaningfulness of the system and about being submissive to it, and there is a hint of regret that the people do not muster up enough imagination and initiative when it comes to dealing with the cumbersome machinery of the state and the obscurity and abstract incomprehensibility of the system. In the story, communication from the high command across wide open spaces buried the truth of its messages in the time it took to cross those vast reaches. And now for these youths of Hong Kong, communication is received through a maze of babble, propaganda, and disinformation. What should be questioned and resisted is not just an emperor who preys on his people, but any remote, nebulous, and impersonal idea of a great common cause used to appeal to and motivate the people, whether that cause is a vast idea of a national rejuvenation, or as in Kafka’s story detailed blueprints for a Great Wall strong enough to serve as a foundation for a new tower of babel. Fight is necessary to secure the dignity of man.

Mr Abelard feels that Kafka’s fascination with the themes of fragmentation and abstract incomprehensibility acquires new meaning right here in Mong Kok. And he now comes read the story as an allegory of the events of Hong Kong. Allegories can divide people in a time of ideological struggle, he knows that. But they can also open up an important moral perspective and offer a timely commentary on the ills of society. Sitting in the protest encampment, he has finished his re-reading of Kafka’s story, but we notice that he does not put the little paperback back on the shelf. He puts it down on the table, open on the first page of “The Great Wall of China” in the hope that others may discover it, and discover themselves in it.

Now we see Mr Abelard stand up, his legs seem a little shaky and he steadies himself and takes out his white handkerchief to wipe the perspiration off his forehead. Then he says a quick good bye to the young couple sitting next to him, and walks quietly out of the study corner inside the protest encampment in Mong Kok. As he now continues his walk in search of new things to look at, he thinks to himself that perhaps, after all, we still have to look at allegory with the eye of faith.

THE END