The curious Miscellaneum of

Dr Westphall

Welcome to my online display cabinet of miscellaneous objects that hold personal appeal, spark my curiosity, and provide revealing glimpses into past history and culture.

(Miscellaneum: from Latin miscere ("to mix"), miscellus ("mixed"); miscellanea: a collection of diverse writings; a mixture of different things.)

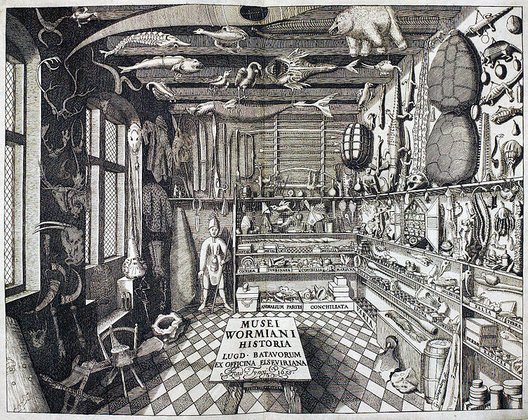

The Museum Wormianum. The Danish physician, natural philosopher and antiquary Ole Worm (1588-1655) gathered a large amount of objects in his cabinet of curiosities in Store Kannikestræde in Copenhagen, including fossils, native artefacts, early literature, and taxidermied animals. The copper engraving is the title page of his four-volume Museum Wormianum of 1655, a foundational work in European museum literature.

- - -

The Miscellaneum is not a collection. A collection is all about structure, limits, and the narrow focus. (The difference between the collector of the specialized subject and the collector who collects everything is that between the sane and the insane). Instead, the gallery of curiosities below is a random gathering and a hoarding. It is highly eclectic, immethodically distributed, and with no chronological arrangement.

Things can communicate a lot to us. Here I use physical objects to understand something about cultures, people, and human forms of communication (communication between people or between people and their god(s)). Walking through the Miscellaneum means to make observations about the environment and context of all sorts of things. It also means to explore in a virtual medium the ‘thingness’ and physical make-up of objects. As we all know, handling and exploring the physical objects can often put us directly and powerfully in touch with the past, whether our own past or that of past people and distant cultures.

The 5 Rules of the Miscellaneum:

- The range of displays is in theory limitless. There are no restrictions of the objects' physical size, age, or use. However, most of the objects displayed are paper objects and ephemera that can be easily handled and conveniently stored.

- The objects displayed must be material objects intended to be touched and handled and serve a specific practical purpose in space and time (a purpose that can be variable as time progresses and different people handle them).

- Variety and randomness are essential to the display and are what make me want to show it.

- The display is entirely subjective; it consists of things that appeal to me (and perhaps only me) and make me want to know more about their background. The miscellaneous items interest me for their historical significance (or insignificance, as the case may be), their material complexity (or simplicity), and for what they reveal about human forms of communication past and present.

- The objects must be in my possession at the time of publishing the display. They must be objects that I have desired and wanted to acquire, either through purchase, exchange, gift-giving/receiving, retaining, or, in exceptional circumstances, theft (I'm not a criminal, I hasten to add...). We are all curators of objects that outlast us; the objects shown here pass through many hands and are adopted at different times into different contexts of meaning and collecting.

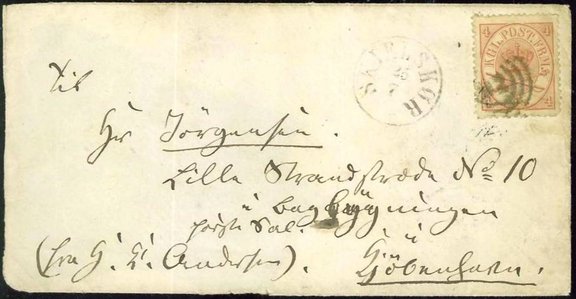

An envelope sent from the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen to his young friend Hans Christian Jørgensen in Copenhagen in July 1867.

The address runs

Til Hr. Jørgensen, Lille Strandstræde No 10, I bagbygningen, første sal, i Kjøbenhavn, (fra H. C. Andersen)

The envelope is without the contents, which is preserved in the Royal Library in Copenhagen and can be read at the website of the Hans Christian Andersen Center, letter id #12829 (http://www.andersen.sdu.dk/brevbase)

H. C. Jørgensen (1847-1869) was a 20-year-old office clerk, unemployed at the time that Andersen writes to him. In the letter, Andersen informs him that he is seeking employment for the young man and has organized a charitable collection of funds among his friends to help support him.

At the time of writing, Andersen resided with Henriette Scavenius (née Moltke) at the manor house Basnæs near Skælskør (100 km west of Copenhagen). It is estimated that Andersen visited Basnæs 37 times and spent more than a year in total at the estate where he found peace and inspiration to compose much poetry and fiction.

When I hold this small addressed envelope I feel that Andersen’s personality shines through, even without the correspondence. His quaint, gothic handwriting is highly distinct, and his common practice of signing the envelope was quite unique at the time. Being an ambitious, attention-seeking, and rather vain individual, he clearly wanted people to know immediately that they were handling a letter from the author Hans Christian Andersen.

Ethiopian amulet necklace, commonly referred to as a kitab (the strap is not original).

This is a small leather pouch (3x3cm) with an embossed pattern in the shape of a cross. Inside it are small scrolls of handwritten text on animal skin containing magic spells in the language of Ge’ez, the ancient liturgical language of the orthodox Ethiopian church. The official Ethiopian church did not recommend or approve of these objects which blend Christian prayer with popular folk superstition. Typically, these amulets contain protections against disease, death in childbirth, and demonic possession.

The small amulet is surprisingly light and I imagine it was carried during the day and perhaps hung by the bed at night. Because the text scrolls have been sewn into the pouch they were clearly not intended to be taken out and read. It would have been carried solely for its protective and curative effects, and the ancient liturgical language of Ge’ez would have been treasured for its holy power to connect human and divine and ward off evil spirits. Ge’ez was no longer a popularly spoken language by the time this amulet was produced, probably sometime in the nineteenth century.

Mao’s infamous Little Red Book, or Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung, printed in China 1964-1976 and the second most printed book in history.

As is typical of Mao’s Little Red Book, this copy is compact and instantly recognizable, with a cover of bright red vinyl wrapped over cardboards. It was a book to be read and memorized, as much as an icon to be carried around and waved as a sign of conformity to the Chinese Communist Party and the personality cult of Mao. Shortly after its publication, the book became a global phenomenon and an emblem of radicalism in many countries. It also stands as a symbol of perhaps the most catastrophic and sustained abuse of power the world has ever seen, by an individual who held absolute power over one-fifth of the world’s population.

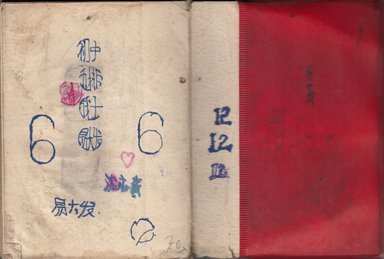

The printing numbers for the Red Book went into the billions. Producing the book pushed printing to its limit and hundreds of printing houses were built all over China. This particular copy was printed October 1966 by The People’s Publishing House in Wuhan in the province of Hubei and it measure 9x13 cm. It is 472 pages long and contains quotations on 36 topics (this is the expanded version of the book; it exists in shorter redactions as well). The binding has split apart and the pages show signs of heavy use with thinned, dirtied pages and much underlining. The front and back end papers show scribblings and ownership markings of a student in middle school by the name of Yi Da Fa; unfortunately the school is unknown, but the student, who must have been between 12 and 15 years old, was in the 7th class and seated on the 5th row, as is noted several places inside the book.

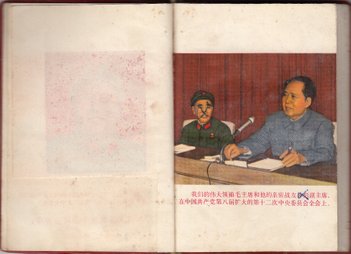

At the front of the book is the usual colour photographs of the chairman. The image of Lin Biao has been crossed out; Lin Biao was once Mao's "closest comrade-in-arms and successor", but he was condemned as a traitor by the Communist Party and conveniently blamed for much that went wrong during Mao's reign.

Scribblings by the owner of the Little Red Book, Yi Da Fa, a student in middle school. The small pink heart reveals more to me about this teenage student than do the many underlinings and handwritten Maoist sentences that occur throughout this much-used book (or maybe the heart is for the Chairman...).

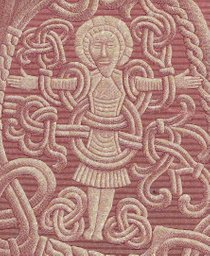

Viking Rus Cross pendant with suspension loop. Copper-alloy with bronze. Found by the Ros River near Kiev in Ukraine. 10th-11th century AD. 4x2,3 cm.

This small cross is associated with the Vikings who explored and settled in the eastern Baltic and the river systems north of the Black Sea. The Greeks and East Slavs knew them as the Varangians. These Scandinavian settlers played an important part in the culture and political organisation of the territory at whose centre were the powerful city-states of Novgorod and Kiev. This particular type of cross is known in specialist literature. According to Kayl and Nechitaylo’s Catalogue of Christian Body Crosses of the Kyivan Rus Period of X-XIII Centuries about 100 copies are recorded and the authors date it to the 10th-11th century. A similar cross is also illustrated in the second volume of Brett Hammond’s British Artefacts - Middle Saxon and Viking (Witham: Greenlight, 2010, pp. 55-56), where it is described as a Scandinavian cruciform pendant also found in the British West Midlands.

I think of this cross as an early form of international relations: it reminds me of the Byzantine iconography (and the Kievan Rus region had rich trade and cultural links with Byzantium); especially it has similarities with early Nordic representations of the Crucifixion such as we see it on the famous big runestones from the royal seat of Jelling in Dernmark (10th century). On both the Jelling stone and the cross pendant we see similar interlace pattern, a cloth that reaches to the knees, a halo with small regular segments, and extended arms with palms openly displayed. But the round and wide-open eyes on the small cross look rather peculiar.

In his British Artefacts, Hammond suggests that ‘the two figures are displayed with enough differences to demonstrate that they are not intended to represent the same individual; since the alpha and omega figure must be taken as the crucified Christ, the other figure in his monastic habit should represent an evangelist, a saint or a cleric.’ I’m not convinced that this is true, and I appreciate the cross especially because I think it leaves something open for interpretation and imagination. I wonder if it is Christ represented on both sides: one side a static, majestic, robed Christ and the other very worn side a bare-chested Christ with head dropping to one side and fingers spread; perhaps this is intended to symbolize the crucified and the resurrected Christ. Or perhaps the better-preserved side shows the Virgin Mary?

The small cross is surprisingly heavy and with the loop intact it is wearable today. It is a bilateral cross, consisting of two halves joined together. I have seen six or seven copies of this cross and I note that nearly every one of them has considerable wear or damage to the same side (the side with Christ with head slanted). Perhaps there is some clue to past uses in this; perhaps this is wear from contact with garment, or perhaps fingers handled this side frequently as part of devout practices…

Christ crucified, depicted on the Jelling Stone of c. 950. The picture is from my Danish pasport.

A Clovis culture arrowhead, found in Tennessee in the United States. Dating from the end of the last Ice Age about 12.000 years ago. 3x6 cm.

If I gently tap on this stone age arrowhead with a light metal object it can give off somewhat of a faint ringing sound. Indeed this type of stone, hornstone or hornfels, is appreciated for its exceptional toughness and capacity to resonate like a bell when struck (in some places the stone is known as “ring stone”). I'm convinced that whoever chipped away at this piece of stone back in the mists of time must have also appreciated this sound.

The sound which the stone makes is the sound of a beginning. These Clovis culture tools provide the first hard evidence we have of human inhabitants on the American continent. As I understand it, they can be about 13.000 years old and possibly older and they have been found all over North America and further to the south; they get the name from the city of Clovis in New Mexico where these points were first discovered in the 1930s.

The late stone age people who produced these artifacts were the ancestors of the modern native Americans, and they were nomads, hunters, and intrepid explorers. The most likely scenario is that people walked from North East Asia across what was then a land bridge to America (Beringia) and spread onto the American continent from around 14.000 years ago. (There is some evidence also of an early migration northwards from South America, so it's possible that we should think in terms of several waves of migration into North America). On the rich hunting grounds that today we call the United States the skilled stone age hunters managed relatively quickly to kills off most of the bigger mammals then present, such as elephants, lions, and mammoths. I often wonder if my small clovis point was once lodged inside a dying animal; perhaps the damage to the point (one broken basal edge) occurred during hunting…

The projectile point is quite beautifully chipped and thinned, and it is still remarkably sharp. I’m certain that it could draw blood if I ran a finger along the edge. This is a reminder that this is of course a killing tool, and a rather efficient one at that: the sharp rugged edges of even a small spearhead like this would cause massive bleeding inside any animal and slow it down, if not kill it off entirely.

A certificate of authenticity has been issued for this object and it notes, in delightful terminology, that it “exhibits surface sheen and stone aging coloration patination and aged mineral deposits”. Click here to see the certificate.

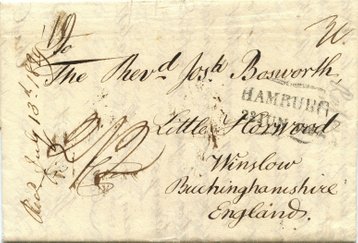

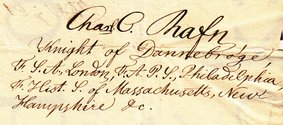

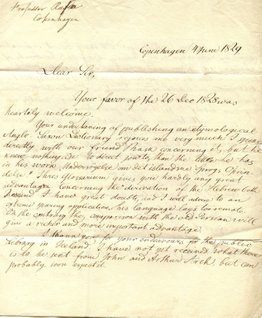

A letter of 1829 from the philologist Professor Carl Rafn in Copenhagen to Joseph Bosworth, compiler of the first Anglo-Saxon dictionary.

An Anglo-Saxon dictionary is a dictionary of Old English, the English language spoken in the British Isles between the fifth and twelve centuries. In 1838 the English scholar Joseph Bosworth (1788-1876) published his famous Dictionary of the Anglo-Saxon Language, the first major etymological dictionary of Old English to appear. In 1829 the Danish linguist and antiquarian Carl Rafn (1795-1864) wrote to Bosworth to congratulate him on his decision to pursue this ‘great and excellent scientifical undertaking’.

Rafn notes that he has consulted Rasmus Rask, another notable Danish linguist, and they recommend the further study of Old Persian, instead of Hebrew, to inform Bosworth’s description of the etymology of Old English. Rafn further updates Bosworth on progress with his publication of ’16 volumes of the old Northern Historical and Mythical Sagas” and with the provision of books for libraries in Iceland and the Faroe Islands.

Besides his endeavours to publish the Norse and Icelandic sagas, Rafn was one of the first scholars to recognise the Viking explorations in North America (referred to as Vinland in the Norse sagas, and for long thought to be merely legend).

Rafn writes in exquisitely crafted English sentences and with an almost calligraphic handwriting, both of which were common features of 19th century letter-writing, not just among the learned elite. While the letter shows the conventions of eloquence and formality of the time, it also reveals the brand of vanity not uncommon among accomplished academics: Rafn inquires about medals he is likely to win from British learned societies and below his signature he lists various distinctions and academic fellowships.

The letter, carefully sealed on the back with red wax, shows the collaborative nature of much academic work, also before the time of frequent travel and instant messaging. It is dated 4th of June 1829 and on the front Bosworth has noted ‘Received July 13th‘.

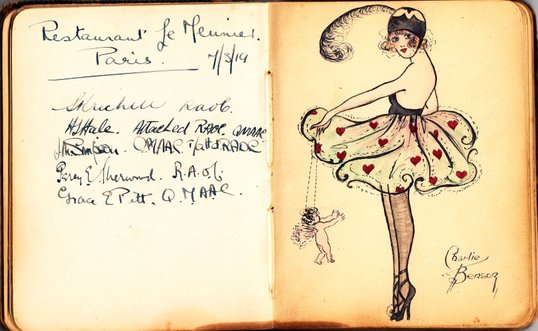

"All dressed up and nowhere to go". France 23/2/1918

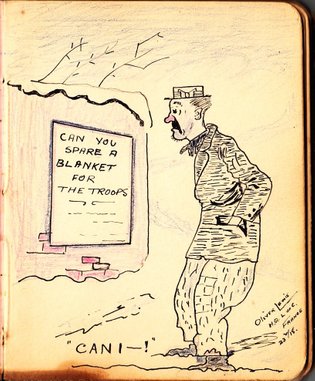

"Can you spare a blanket for the troops?

Can I!"

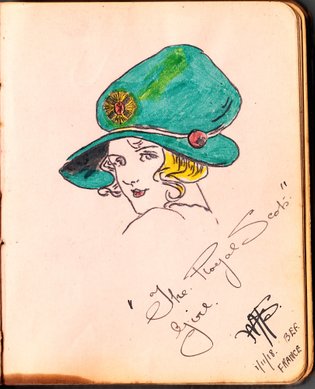

"The Royal Scots Girl"

France 1/11/1918.

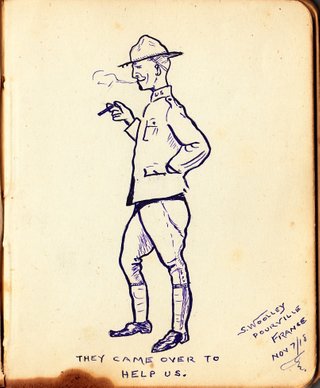

"They came over to help us"

Pourville 7/11 1918.

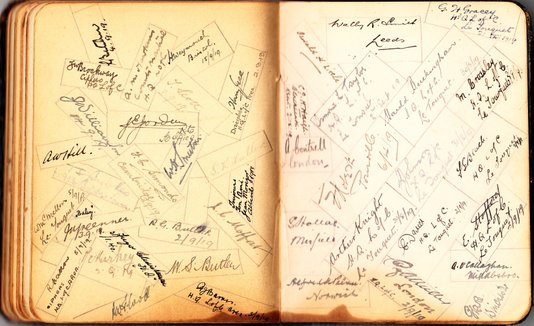

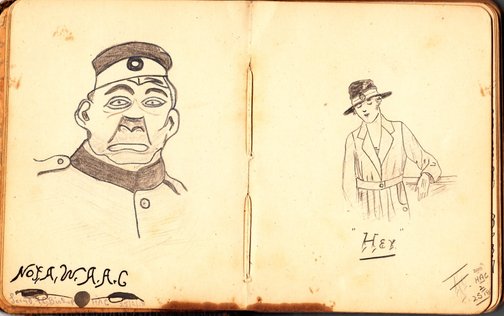

An autograph book of a member of the British WAAC (Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps) stationed in Northern France at the end of the First World War, 1918-1919.

The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps was the women’s branch of the US and UK armies. Established in 1917, the purpose was to compensate for a shortage of manpower and to free up men who did “softer jobs”, so they could be sent to the front. The women in the WAAC were mostly employed for administrative duties, and as cooks, telephonists, and instructors (for example in the use of the gas mask).

This autograph book belonged to Grace E. Pitt of the British WAAC. The book contains about fifty inscribed pages dated between February 1918 and September 1919. Most of the entries were written in the towns of Abbeville, Pourville, and Le Touquet, all in Northern France, and were written by people with the WAAC, MTASC (Motor Transport Army Service Corps) and the RASC (Royal Army Service Corps).

Most of the entries in the small book are signed by each writer and dated with a note of location. Some contributors have added their signature or a short illustrated witticisms (for example, a black ink stain is described as “a black man’s tear”, and a French postage stamp stuck to a page has the heading “By Gum it Sticks!”). Other entries take the form of drawings (some rather good), cartoons of various figures and military personnel, comic verse, and small verse of this sort:

If scribbling in albums

Friendship secures

With the greatest of pleasure

I’ve scribbled in yours

The autograph book is a record of people met and friendships formed during military service. The content is light and humorous throughout.

This makes me think of this book as a euphemism for the tragedy of the First World War: the owner was stationed in Abbeville and Le Touquet where there were military hospitals for British troops wounded in battles such as those in the Somme and Ypres, but there is nothing at all to indicate the horrors of trench warfare or the use of poison gas on the battlefields.

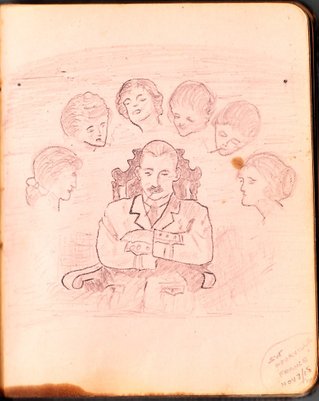

A dapper gentleman reminisces about the ladies he has loved?

Pourville 7/11 1918.