The correspondence of the British missionary W. H. Medhurst, 1796-1857

The English Protestant missionary Walter Henry Medhurst (1796-1857) travelled as a missionary in the Far East from 1819 till 1856. Because foreigners were prohibited a long time from conducting trade and missionary activity inside China, efforts were concentrated first on overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. Medhurst worked first from Malacca, then the headquarter of the English Chinese mission, and Penang. 1821-42 he ran the Java mission located in Batavia, and from 1843 he settled in Shanghai.

Medhurst's approach to missionary work was characterized by a proactive, itinerant form of evangelizing which brought him into contact with the locals and resulted in deep familiarity with local customs and languages and dialects. He was also an energetic writer, manufacturer, and disseminator of religious tract literature. His training in his young years as a printer and typesetter was put to good use in the Far East.

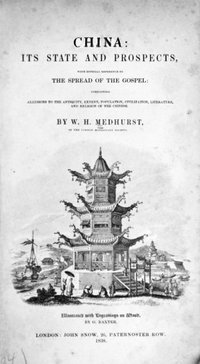

Medhurst published widely in English on Chinese history, culture, and topography, and his several books provided English-speaking audiences with much knowledge about the unfamiliar region.

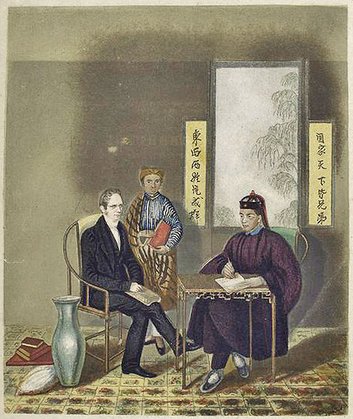

Medhurst in Canton with Choo Tih Lang and a Malay boy. The illustration is the frontispiece in Medhurst's China: Its State and Prospects (London: John Snow, 1838).

W. H. Medhurst, China: Its State and Prospects (London: John Snow, 1838)

For Medhurst and his colleagues, bringing Christianity to the Chinese proved a tough sell! According to Medhurst, two of the chief obstacles to foreign missionary activity in China were a Chinese feeling of cultural superiority, which made them unlikely to warm to Western Christian values and education, and unfamiliarity with communal forms of worship. Jane Kate Leonard provides the following assessment of the Christian mission in China:

It was clear even to the novice missionary that the Christian religious message had no meaning or significance to the Chinese. A tract that was narrowly religious and devotional in content held no interest because of the vast cultural and historical differences between China and the West. Medhurst felt that these differences were responsible for the inabilities of the missionaries to attract a Chinese following, and he often "sadly lamented his own want of success" in converting Chinese during his early years in Java. He pointed out bitterly that, although the Chinese showed great eagerness to possess the tracts and translations of the Bible that the missionaries handed out, this was no proof of religiosity or interest in Christianity. On the one hand, it demonstrated the Chinese respect for the written word and literacy; on the other, it reflected the typical Chinese enthusiasm for getting something foreign for nothing.

J. K. Leonard, 'W. H. Medhurst Rewriting the Missionary Message', in Christianity in China: Early Protestant Missionary Writings, ed. by S. W. Barnett and J. K. Fairbank (Harvard UP 1985)

The sense of disillusionment with the China mission is evident from the Medhurst letter from 1842 below. Increasingly, Medhurst turned to education and writing on secular matters, aimed at both Chinese and English audiences.

The Medhurst correspondence

Walter Medhurst, like many of his fellow missionaries, was a prolific letterwriter. He sent substantial bi-annual mission reports to the London Missionary Society, in addition to regular mission accounts, business letters, and letters to friends and relatives. The biggest collection of Medhurst letters is in the archives of the London Missionary Society presently held at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Occasionally missionary letters are offered for sale to private collectors at auctions for stamps and postal history. I have five Medhurst letters in my collection of Dutch Indies postal history (and I'm always searching for more!).

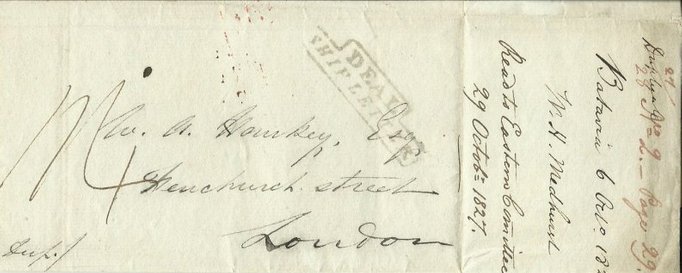

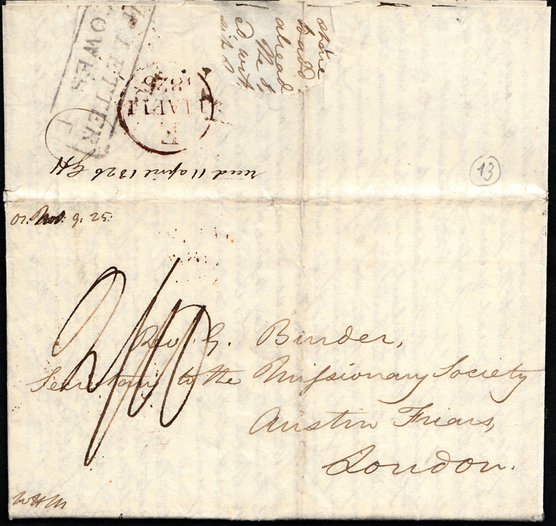

Batavia 6 October 1826 to London, received 21 July 1827 (it took more than 9 months for the letter to reach London!).

In the letter, Medhurst informs on his signing on bills to the amount of 100 pounds 'in favour of Messrs. Thompson, Roberts & Co. of this place'. Thompson, Roberts & Co. was a Batavia forwarding agent who facilitated the routing of international mail before the full development of the postal system.

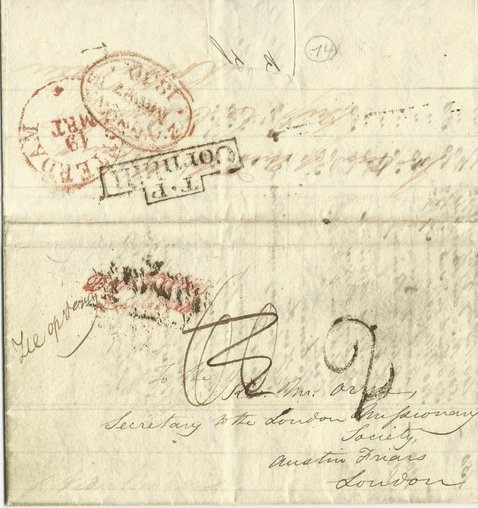

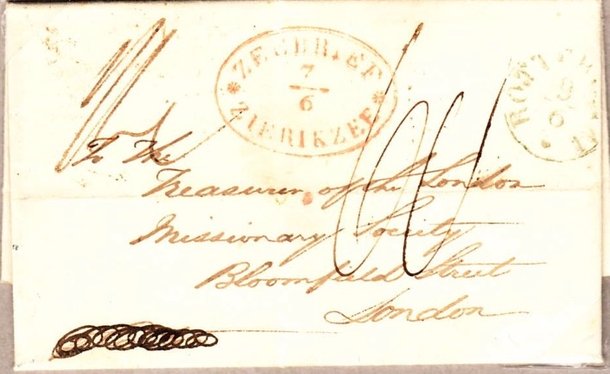

Letter sent from Batavia 9 November 1829 to the Secretary of the London Missionary Society. Sent via Den Helder ('Den Helder Zeebrief' cancel on front) and Rotterdam 19 March 1830. On the back is a handwritten notation probably referring to a forwarding agent; ‘Rotterdam’ is legible but the ink has faded too much for the rest to be read. Also on the back is a TP/Cornhill receiving office postmark and the London receiver of 27 March 1830.

In the letter, Medhurst is hopeful that, in the wake of the Opium War, China may become open to foreign missionaries. Ever since he ventured out to the Far East in 1819, Medhurst intended to perform missionary teaching inside China: a few months after he sent the above report he transferred to Shanghai where he founded the London Missionary Society Press with several of his associates.

We are waiting here with intense anxiety to see what will be the result of the movement at present made in China. From whatever causes the nations of the earth drive together we know that the loss of all can overrule their contests to his own glory and the extension of his kingdom. Long enough has China been sealed against the efforts of his servants, and rejected with pertinacity the messages of mercy to her sons: it is now however come within the verge of both possibility and probability that the middle wall of partition will be broken down and that the great trumpets shall be blown through the length and breadth of the land proclaiming liberty of the captives and the opening of the prison to them that are bound and to proclaim the acceptable fear of the lord. We long to be among the foremost when peace is proclaimed and a quiet settlement secured, to visit her border and carry out a work in the preparation for which almost a life has been spent.

In this letter from 1829, Medhurst provides a brief update on the news of the missionary station in Batavia. At this stage, Medhurst had been active as a missionary in Java for 8 years. He notes the following about a planned expedition to Bali:

‘It is our intention (God willing) to undertake another missionary tour, to the eastward, as far as Sourabaya, or perhaps Bali, which island has never yet been visited by missionaries, and where we hope to put in circulation a tract lately printed by Mr. Buckner, at Serampore, which being in the Javanese language, will be understood by the Balinese also.’

The rest of the letter provides the London Missionary Society with the Batavia mission accounts from July 7th to October 31st 1829. Besides the listed salaries for Medhurst and associates, the main part of the accounts pertains to books and printing equipment, such as ‘lithographic printer 1 month’, ‘implements for block printing’, ‘500 tracts on Jesus’, ‘300 village sermons’, ‘paper for printing’, 'ink’, etc.

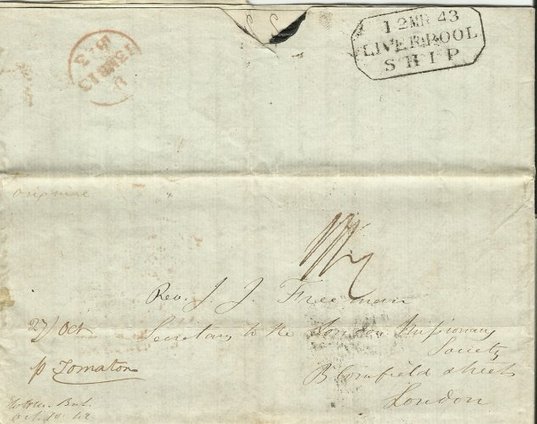

A six-page report on the mission activity in Batavia dated 10 October 1842 and received in London 13 March 1843. Dating to the final moment of Medhurst's work in Batavia, the letter provides a rather bleak outlook on the affairs of the Christian mission; as he remarks, his report will

afford little interest to those who long to hear of rapid advances and frequent accessions to the cause of Christ. The work of a settled missionary, however, must be of rather uniform character when fulfilling the statedly recurring duties of his chapel & school, he has nothing to report but the continuance of those labours, and an occasional addition to the number of the faithful.

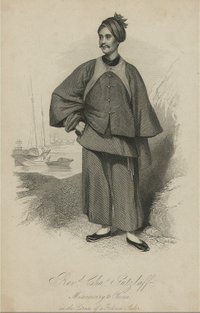

A major portion of the letter reports on progress with the printing of religious tracts. Medhurst is noting the arrival of a full set of Chinese printing types 'sent out I believe by the King of Prussia to the missionary Gutzlaff which he has placed for the time in our printing office for the purpose of printing Chinese books and tracts.' The Gutzlaff referred to here is the German missionary famous for wearing Chinese-style clothing, and for his several popular travel books. The letter continues to give a detailed account of the many religious texts recently printed on the Batavia press and of their circulation throughout Java and beyond.

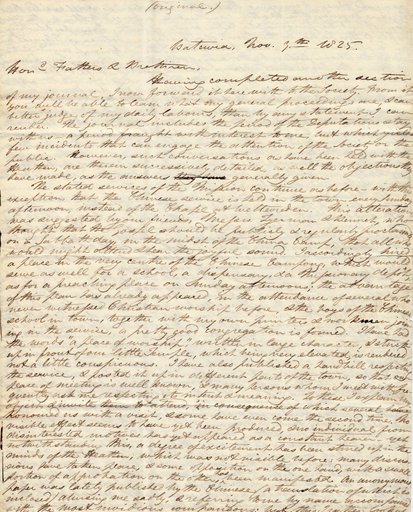

A mission report from Medhurst from November 1825, sent back to the Society in London. The letter contains nothing particularly surprising in its contents, but it is nevertheless exceedingly interesting for the details it provides on missionary work in Batavia.

The letter reveals that Medhurst, working in Java at the time and for the next eighteen years, focused primarily on missionary work among the Chinese population. He informs the brethren in London that he has moved the services of the Mission from the chapel in the district of Weltevreden into the centre of Batavia, in order to be at the heart of the Chinese ethnic community, and to have a place (‘a little temple’) that could also serve as school, dispensary and missionary depôt. He also acknowledges receipt of a box of books from London, including Arabic books and a Koran, but states that he prefers to focus on studying Chinese culture and language and printing books in Chinese. At a later stage he intends to study the Koran, as he puts it, ‘to set to the work of undermining the strong holds of the false Prophet, and exposing some of the manifest errors of Mahomedanianism.’

That the task of engaging the Chinese community was far from unproblematic is also evident from the letter, which notes the circulation in Batavia of malicious Chinese propaganda against the Christian mission and Medhurst's own person (‘making the most invidious comparisons’). Never a person to sit on his hands, Medhurst will promptly publish a reply in Chinese, written in the form of a dialogue between a Chinese and an Englishman, in which he answers all objections and proves the superiority of his faith.

Finally, Medhurst considers discontinuing the English-language service in Batavia because of dwindling numbers of British. However, as long as half a dozen attend he is determined to continue, not least for the spiritual needs of his own family.

The indomitable and highly eccentric German missionary Karl Gutzlaff (1803-1851) in the traditional costume of Fujian province. Gutzlaff collaborated with Medhurst and a few others to produce a full translation of the Bible into Chinese. Gutzlaff is the subject of a fascinating biography by Jessie G. Lutz, Opening China: Karl F.A. Gützlaff and Sino-Western Relations, 1827-1852 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008)

Batavia, November 9th, 1825. A page of Medhurst's densely written missionary report, sent from Batavia to the Missionary Society in London.