A postcard in Volapük

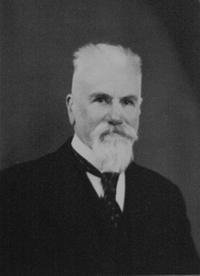

Arie de Jong 1865-1957

The life of Arie de Jong would undoubtedly make for an interesting biography. Born in Batavia in 1865, he studied medicine in Leiden, and in 1892 he returned to the Netherlands Indies to play a key part as a medical officer in the Dutch efforts to combat tropical diseases. While in the Indies he was stationed in many places on Java, Sumatra and Borneo, as well as in Makasser and Bonthain on the island of Sulawesi. Fate dealt de Jong some severe blows: his first wife died onboard the ship en route to the Dutch Indies in 1892, and his second wife and two children all died while in the Indies. In 1919 de Jong returned to the Netherlands and eventually settled in The Hague with his third wife and their three children.

In Leiden, de Jong became familiar with the constructed language of Volapük, developed by the German cleric Johann Martin Schleyer in the early 1880s. At the age of 25 de Jong obtained his Volapük instructor diploma, and for most of his adult life, he was dedicated to the revision of Volapük and its propagation as a universal language. In the 1920s he offered his revision of the language, his ‘Volapük Nulik’ (New Volapük), with a much simplified grammar and refined vocabulary. This reformed version became the standard for the community of speakers.

Among the many achievements of this enterprising Volapükist are:

the foundation of the Dutch Universal Volapük Club

an independent newspaper in Volapük (published 1932-63)

the Gramat Volapüka, a complete grammar of the language

a thorough revision of the German-Volapük dictionary, Wörterbuch der Weltsprache (World Language Dictionary)

a translation of the New Testament from Greek into Volapük

A postcard written in Volapük, sent by Arie de Jong in 1897 to a fellow Volapükist in Belgium. At the time, de Jong was stationed in the Atjeh province in the north part of Sumatra: the card was written in the small settlement of Poeloe Poras and sent from the post office in Olehleh. Unusually, it went via both postal agencies of Penang (23/7 1897) and Singapore (26/7 1897), and onwards to Europe by the French paquebot.

Volapük

Menefe bal – püki bal (One mankind – one language)

Johann Schleyer constructed the language of Volapük with a vocabulary based on English, German and Latin. In the 1880s and 1890s Volapük societies sprang up all over Europe, but ultimately it was the artificial language of Esperanto which acquired more followers.

Schleyer published five editions of his German-Volapük Volapük-German dictionary between 1880 and 1897. In 1931 Arie de Jong presented his heavily-revised version of this work which reflected his own reformed version of the ‘New Volapük' (Volapük Nulik). De Jong’s dictionary was reprinted in 2012 (Cathair na Mart: Evertype), and the foreword to this edition notes that an English translation of the Volapük-German part of the dictionary is currently being prepared.

The language of Volapük was always subject to some ridicule: in Denmark we continue to use the word ‘volapyk’ to describe gibberish and incomprehensible speech. Certain factors worked against the artificial language, such as the short words with heavy use of umlauts, the generally unfamiliar look of words, and the very elaborate grammar (though simplified by de Jong). However, a dedicated group of Volapükists continue to keep the language alive today. The Volapük version of the online encyclopedia Wikipedia contains 119,131 articles as of March 2014 and ranks as number 43 among Wikipedia language edition (thanks largely to one ardent Volapükist who generates large amounts of electronic translations in order to promote the language).

The longest (wordiest) postcard ever written?

On the 18th of October 1888 a lady by the name of Jola in Ambarawa in Central Java put pen to paper and wrote a fabulous postcard. Writing to her parents in Prinsengracht in the heart of Amsterdam, she managed to accommodate between 850 and 900 words on the card in her small delicate handwriting. Her parents must have had exquisite eyesight - or a strong magnifying glass! Unfortunately my Dutch is not good enough to provide a translation.

Jola intended the card to go via Brindisi and by land to Amsterdam, but alas she had not paid enough. The 5 cent rate only paid for the slow route by steamer to the Netherlands and it took two months for the card to arrive. It arrived just in time for Christmas 21/12 1888.

a lovely bouquet of flowers from Jola to her parents.